Post by fots2 on Dec 16, 2012 17:06:03 GMT 8

Along with the big guns, one thing that continually draws me to Corregidor Island is the “Malinta Storage System” commonly referred to as “Malinta Tunnel”. I have no idea why it fascinates me but I have spent hours wandering around the complex. No doubt part of the attraction is the ‘unknowns’ that even after collecting all this information, still remain. In the past while searching for Malinta Tunnel information I rarely found more than a couple paragraphs and most of that was incorrect. I thought it was time to piece the scraps together for anyone else who may be interested.

While trying to research this subject, I encountered the usual cases of disagreeing information so what I present here is a summary based on what I understand to be correct. I consider the most reliable information to come from the US Army’s ‘Corps of Engineers’. This includes correspondence, official blueprints and Records of Completed Works. These are factual records recorded by Army Engineers as the work progressed. Various books were a secondary source.

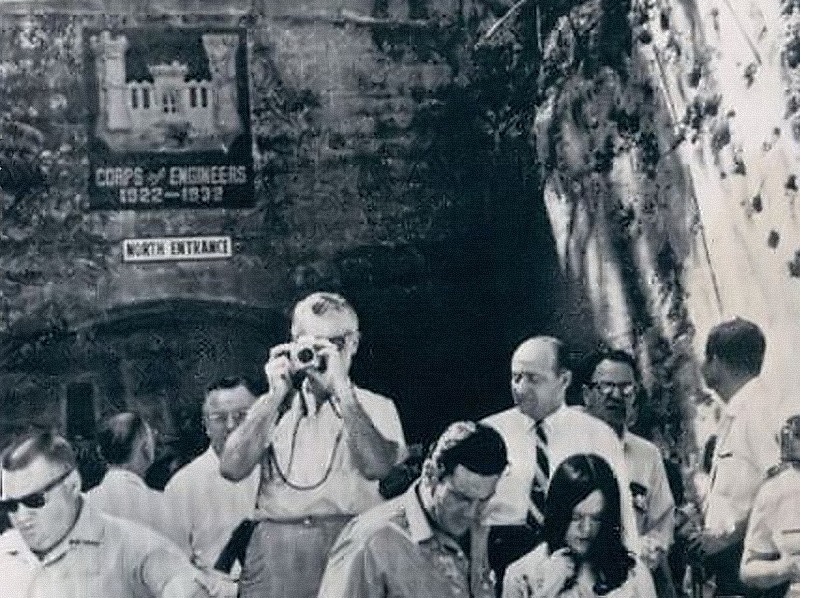

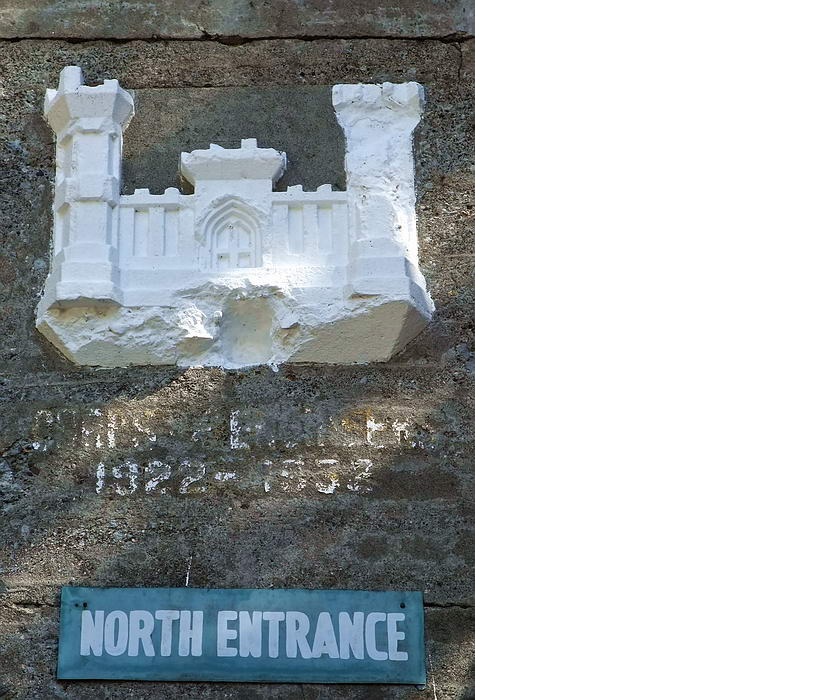

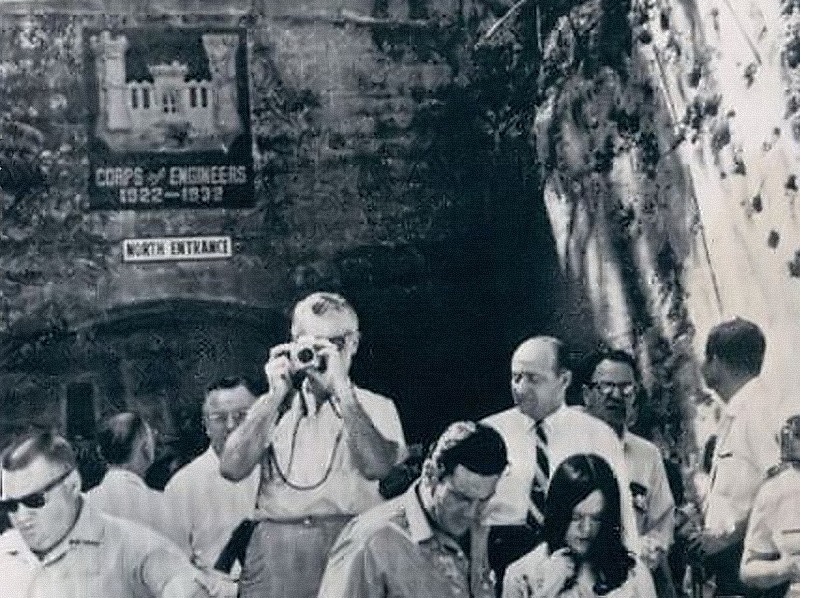

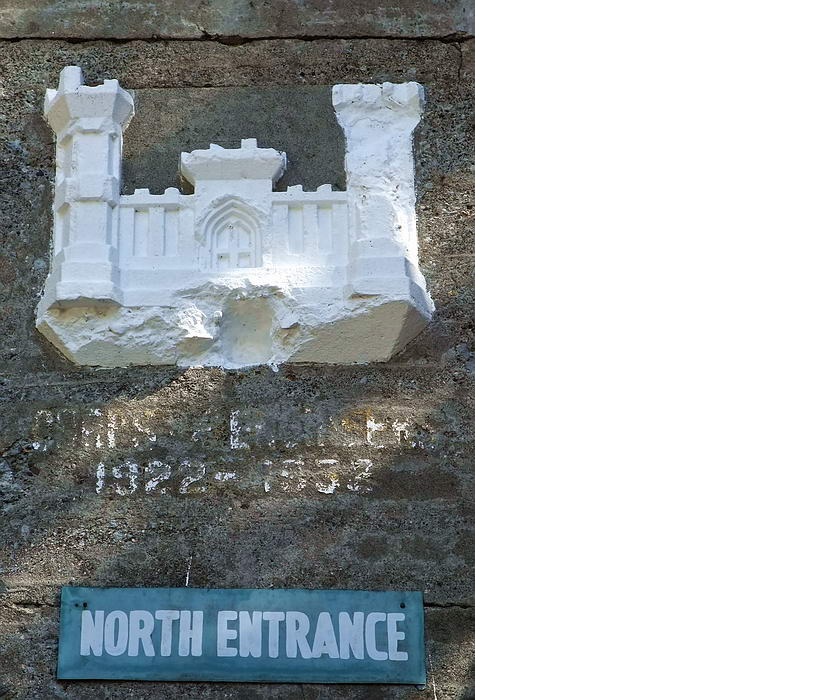

By far the biggest (and widely accepted) misconceptions are the tunnel construction dates. Numerous internet searches plus books and articles state that the Malinta Tunnel was built during the ten year period between 1922 and 1932. These dates are also quoted daily to tourists who visit the island. I can see where this idea may have come from though. One of the tunnel entrances has these dates stenciled on it. The source of this information is unknown.

Zf857. 1966 photo of the Malinta Tunnel North entrance with the wrong stenciled construction timeline information

A photo of the same partially repainted entrance taken two years ago.[/span]

Inaccurate history has become accepted history! I have learned that absolutely no construction took place during this period. For this project, not a single rock was disturbed on Malinta Hill. The correct period starts later in 1932 and continues in several phases up to and including wartime.

Part 1: The Malinta Tunnel from Concept to Completion

Post WWI, the Army realized that Corregidor’s fortifications and defenses were inadequate should a future war break out. This prompted the creation of elaborate plans to rectify these concerns. Two items topping the list were additional storage which was to be bombproof and protection from potential Japanese gas attacks; the idea for a large tunnel under Malinta Hill was born. Driven by Fort Mills commander, Brig. Gen Richmond P. Davis, the Quartermaster Corps drafted a proposal. Here are excerpts from that document.

May 26, 1921

From: Quarter Master Corps Office, Head Quarters, Philippines.

To: Colonel Eltinge,

Subject: Malinta Hill Tunnel proposed for Fort Mills.

Paragraph No.1 mentions:

In the Annual Estimate from Fort Mills, recently submitted, there was included a proposition to tunnel Malinta Hill and provide bomb proof storeroom leading from this tunnel. The entrance to the tunnel would be in the neighborhood of the present rock crushing plant and would extend through under the hill to connect with the tactical road leading to Kindley Field (the new Air Service project) and to the defenses on the tail of the island. It is proposed to make the tunnel about 650 feet long, 16 feet wide and 19 feet high. The roof will be arched. The tunnel would have concrete walls, roof and floor. The tunnel would be placed on a grade so that natural ventilation would result.

1) A single trolley line is planned for the original installation but space is provided so that a double track may be installed later. Four storerooms are to lead from this tunnel, each storeroom to be 40 feet by 80 feet in the clear with an arched roof and concrete lining. Lighting, drainage, and ventilation would be provided for these rooms as well as light for the tunnel.

2) The bomb-proof storerooms would be invaluable in time of war and the tunnel could be used as an emergency hospital. There is no bomb-proof storage for supplies available, and Malinta Hill is the logical place for such a base. This hill is ideal for bomb-proof storerooms and magazines. It is adjacent to the terminal and in time of war could be entirely honeycombed with underground storerooms.

3) The present road around Malinta Hill that furnishes the only good road to Kindley Field and the tail of the island is so situated as to be easily rendered useless by a shell striking any part of the South slope of the hill. Further, this road is exposed to the open sea and is likely to receive shell fire from long-range guns of ships making an attack.

4) The post people state further that the rock taken from this tunnel would be utilized in the repair and maintenance of Post Utilities. There would thus be a slight saving in the construction because it would not be necessary to dispose of the material excavated.

5) The estimated cost of this work is $650,000.00. It is understood that this estimate was carefully prepared by the post authorities and no doubt is approximately correct. Some changes may be necessary in the sizes of the rooms that will result in a slight change of the estimated cost.

6) The arguments for this storehouse are essentially tactical. The reasons become apparent when a study of the storage facilities of the entire island is made. There is no question that additional storage must be provided generally, and it appears that it would be more logical to make bomb-proof space at somewhat additional costs than to place storehouses in the open that are likely to be destroyed during hostilities at the time supplies will be needed.

W. A. Danielson

Assistant Quartermaster

Unknown to General Davis, an event on the other side of the world would soon derail his tunnel plans. Due to fears of a naval arms race in the lean post WWI years, a conference would soon be held in Washington. The five primary naval powers (USA, Great Britain, Japan, France and Italy) attended along with observers from several other countries. The conference started in November of 1921 and concluded with the signing of a treaty in February of 1922.

You may be wondering, what does a naval ship limitation treaty have to do with an Army fort called Corregidor? Well, it appears that the Japanese were reluctant to sign the treaty so the US offered them an incentive. The result was Article XIX which was in effect, a Non-Fortification Clause. It stated that there would be no strengthening of American seacoast installations beyond the 180th parallel of latitude. (i.e. west of Midway Island). Any new armament or defensive improvements to Corregidor were “on hold” until the treaty expired on December 31st, 1937. The Malinta Tunnel project was halted.

A positive turn of events occurred when Brig. Gen. Charles E. Kilbourne assumed command of Harbour Defense in 1929. With very limited funds he began a series of work projects to improve Corregidor. Roads were widened, trees planted, barracks upgraded and Topside got a new swimming pool adjacent to the Officer’s Club. One tunnel near Battery Wheeler was also completed but this work was kept quiet.

In December of 1931, Kilbourne revived the idea of a tunnel under Malinta Hill. Although he had much wider ranging plans than were originally proposed, he only told his superiors he would build a tunnel through the hill to extend the streetcar line towards Kindley Field. Since the North and South Shore roads around Malinta Hill were dangerous due to rock fall then this would save lives. He would not require funds from Washington and tunnel rock would be crushed and used elsewhere on the island lowering future maintenance costs. If anyone in the US knew the details of what Kilbourne was doing then it was kept secret. Washington approved the tunnel project and final plans were initialed by Kilbourne on January 14th, 1932.

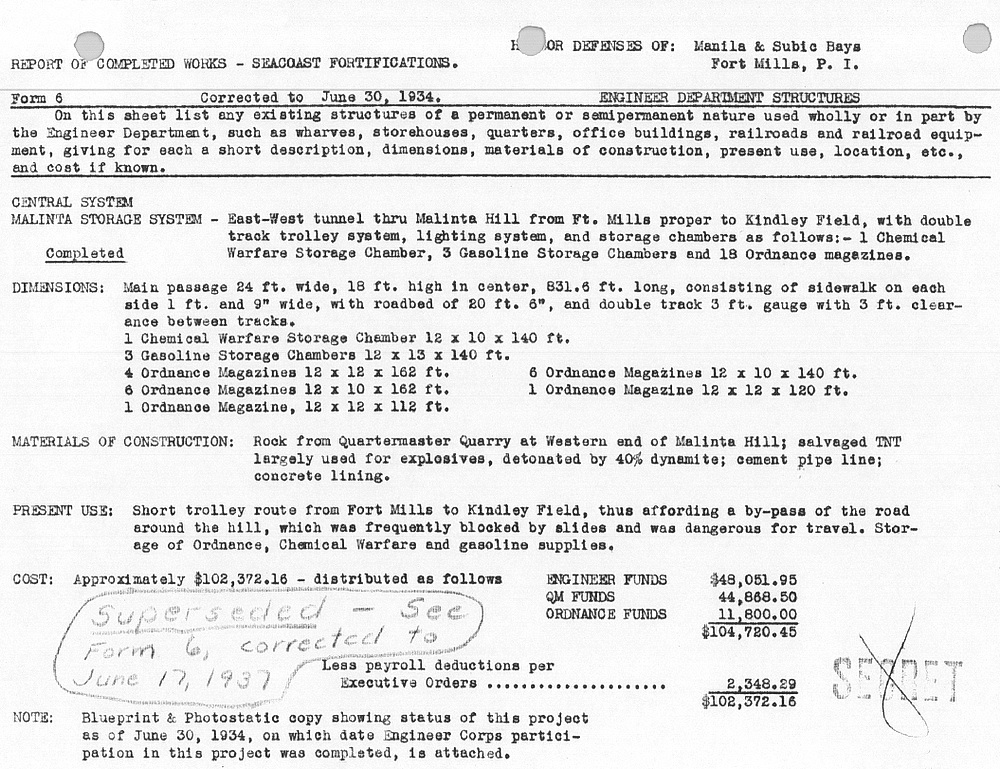

The initial 1921 requirement of four underground storerooms was abandoned and a much more elaborate complex was designed. It would allow for bomb-proof storage of ammunition and supplies in addition to being a gas-proof shelter. In wartime it could also function as a hospital and HQ. (Note that this gas-proofing was never completed). The allocation of central system storage laterals would be; 1 for Chemical Warfare, 3 for Gasoline and 18 for Ordnance.

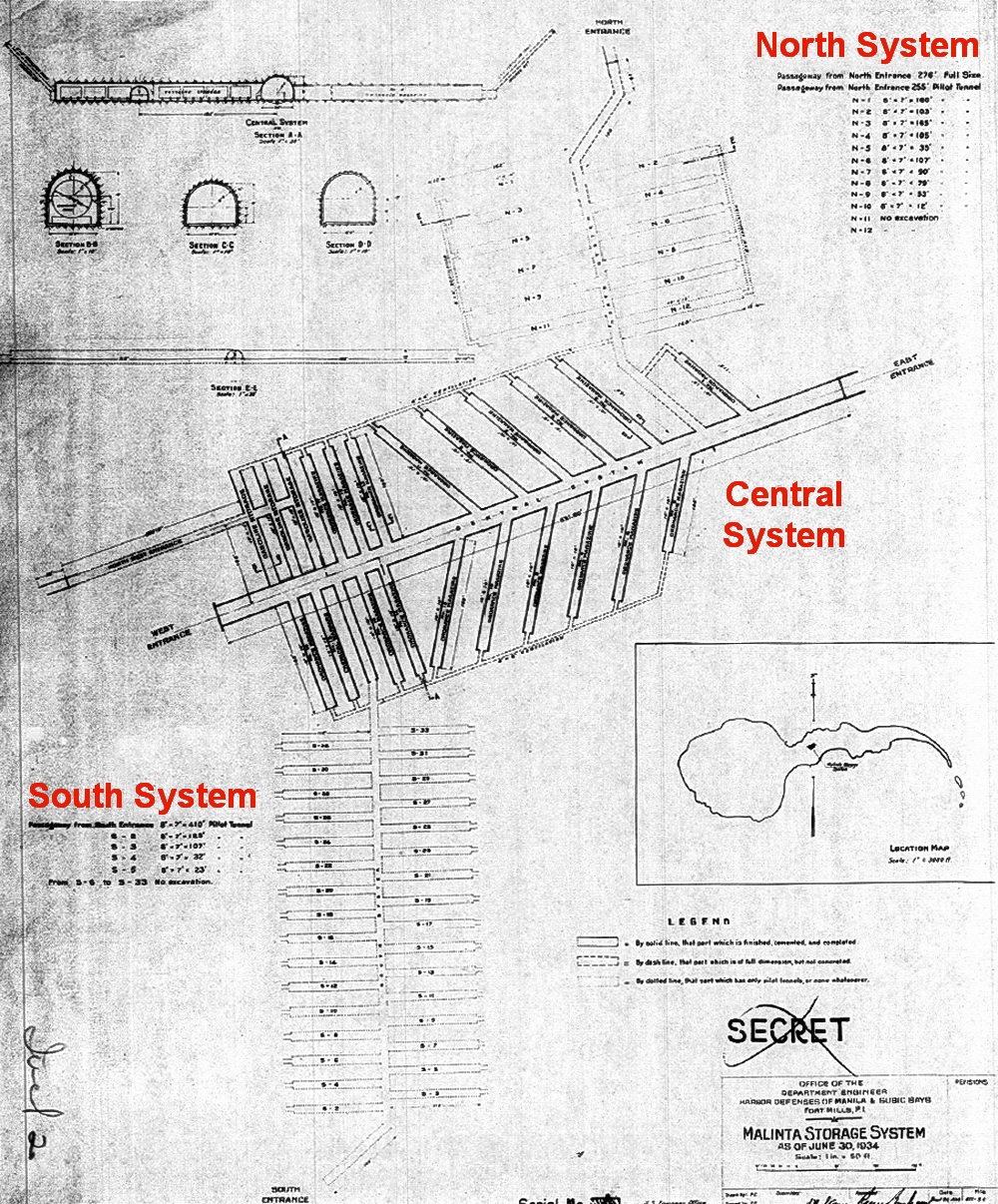

Along with the central system laterals, north and south systems would also be constructed. The North System would have 12 storage laterals and the South System for the QMC would have 32 laterals. In addition to being connected to the central system, both the North and South systems would have a second entrance.

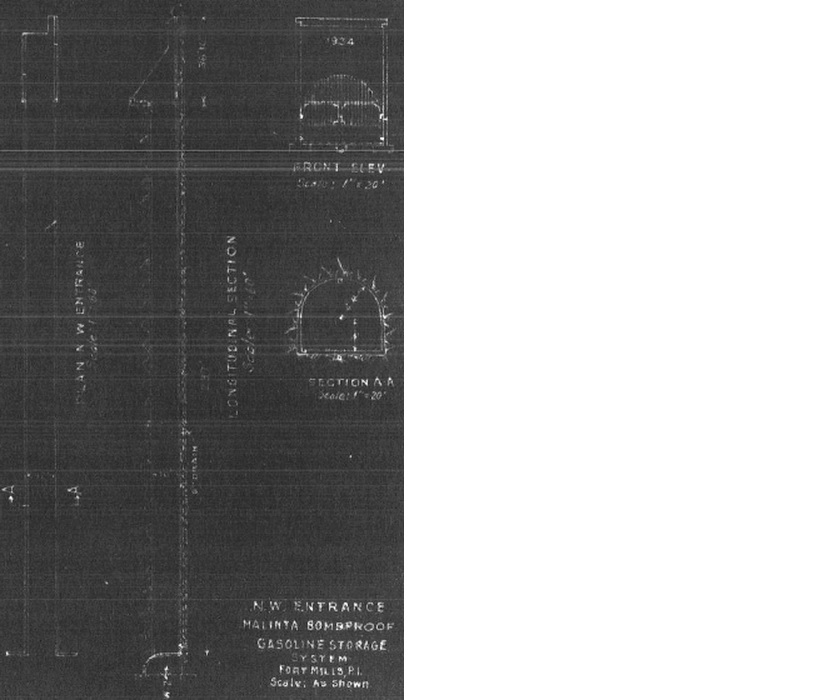

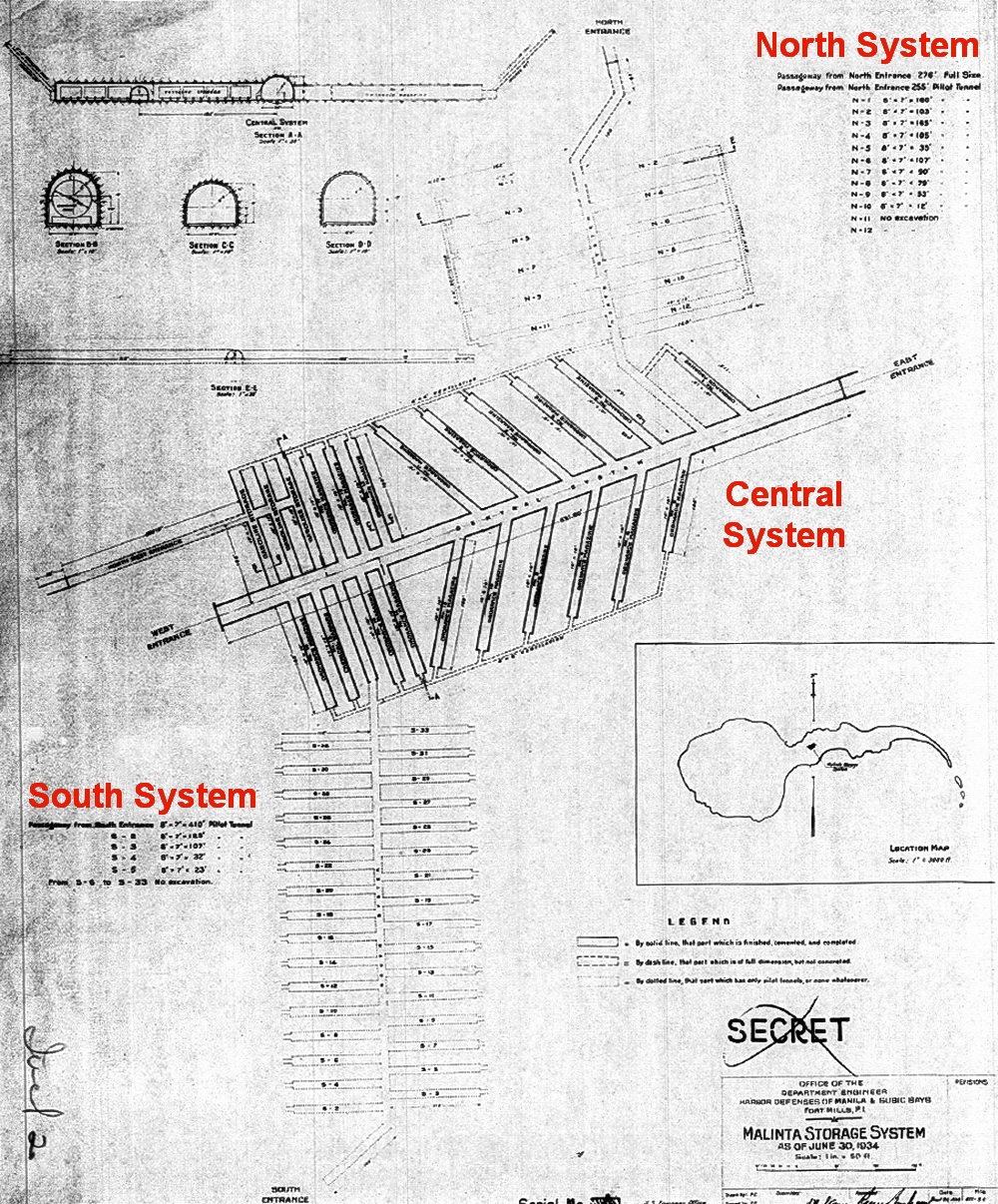

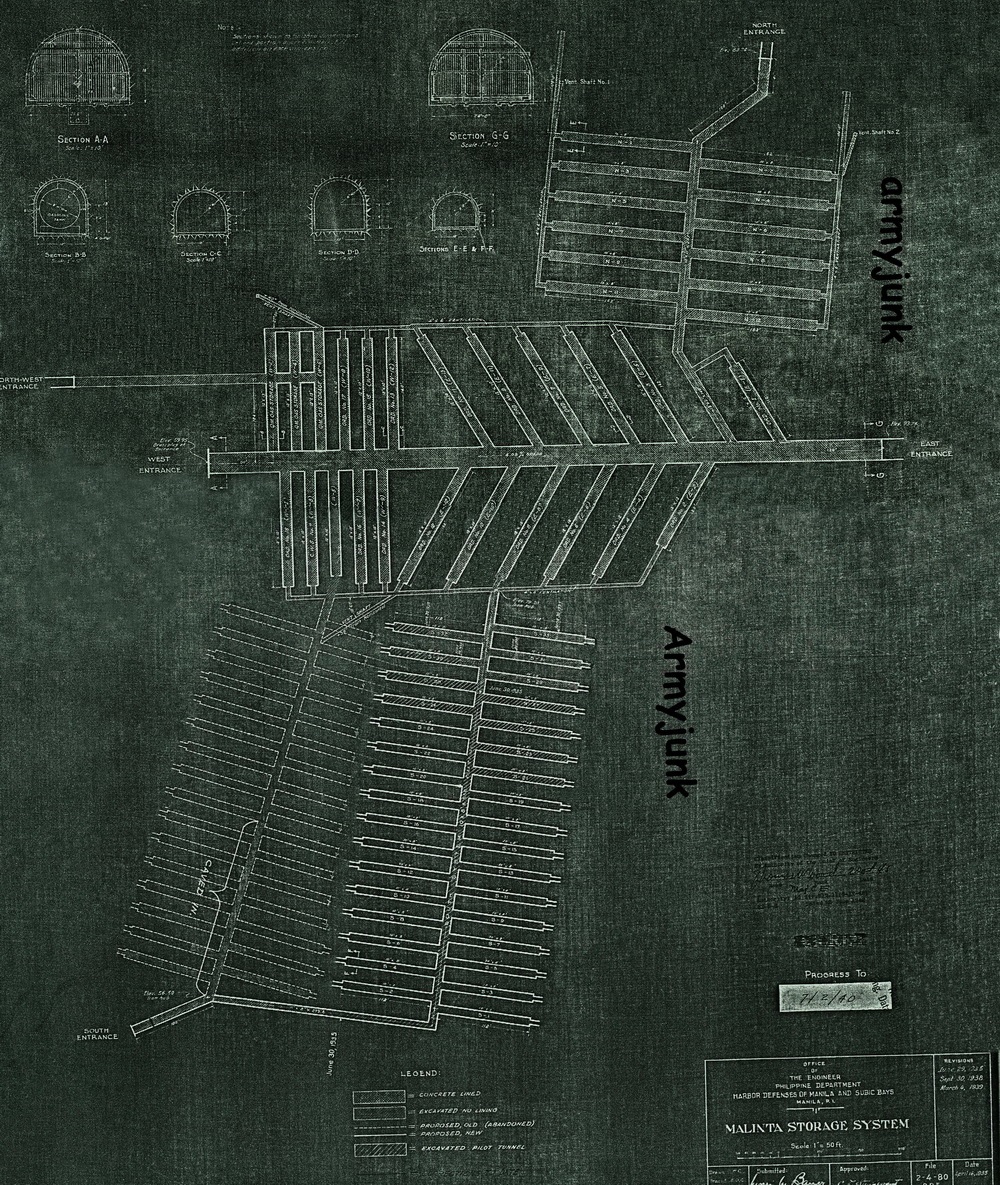

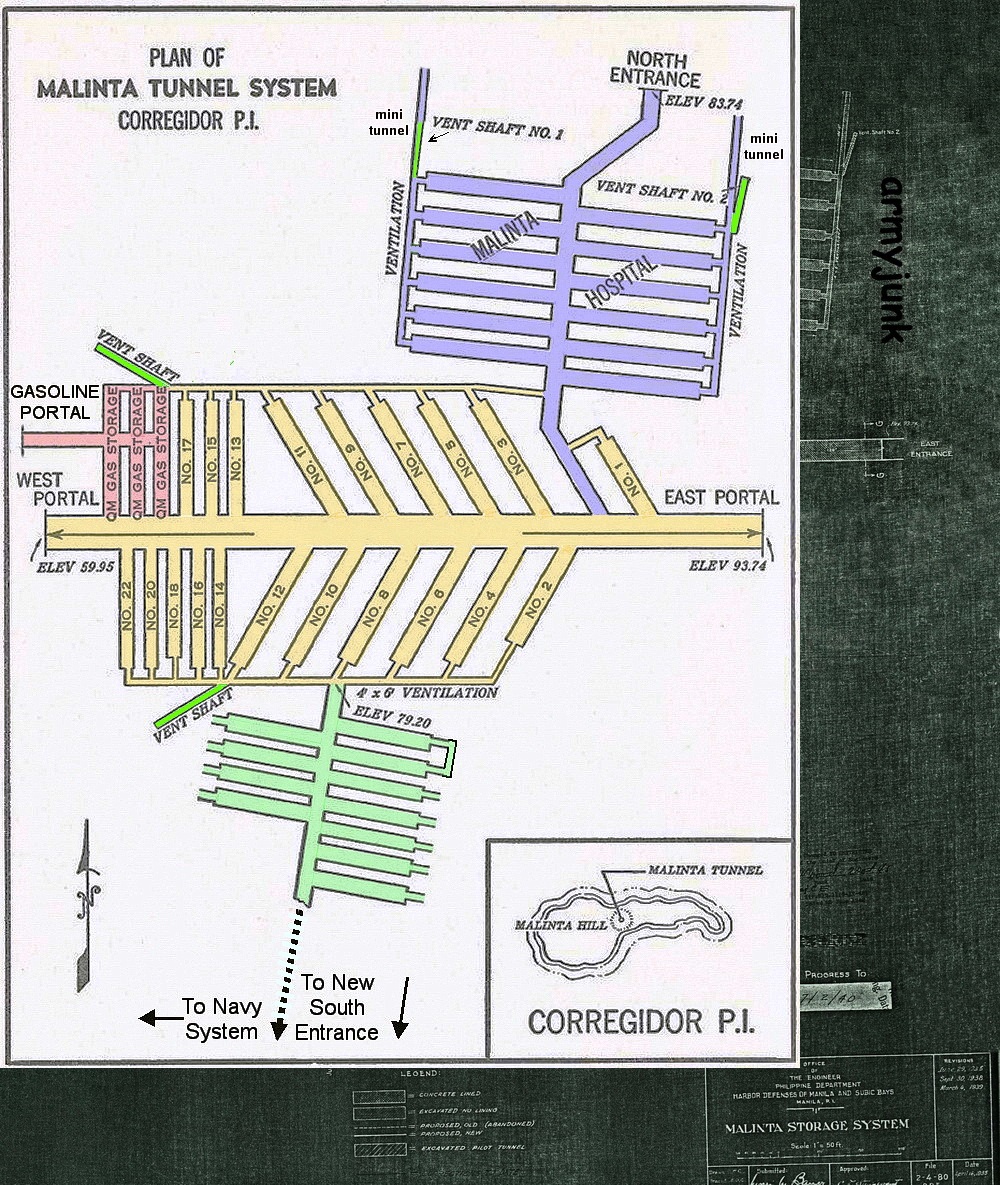

Zf859 Malinta Tunnel System map dated 1934 showing the overall design and construction to date.

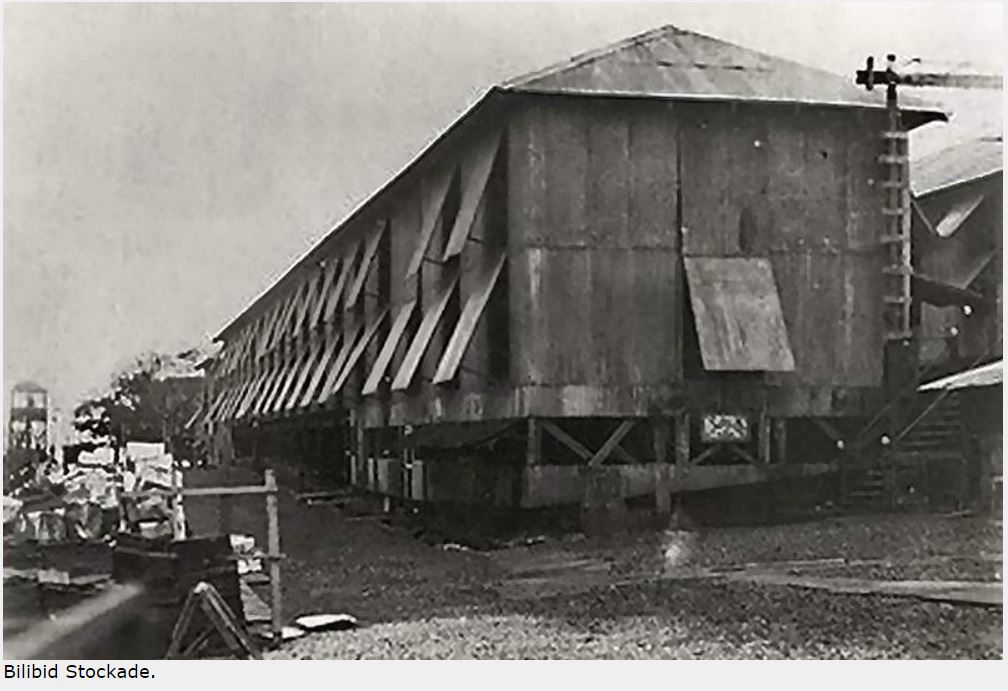

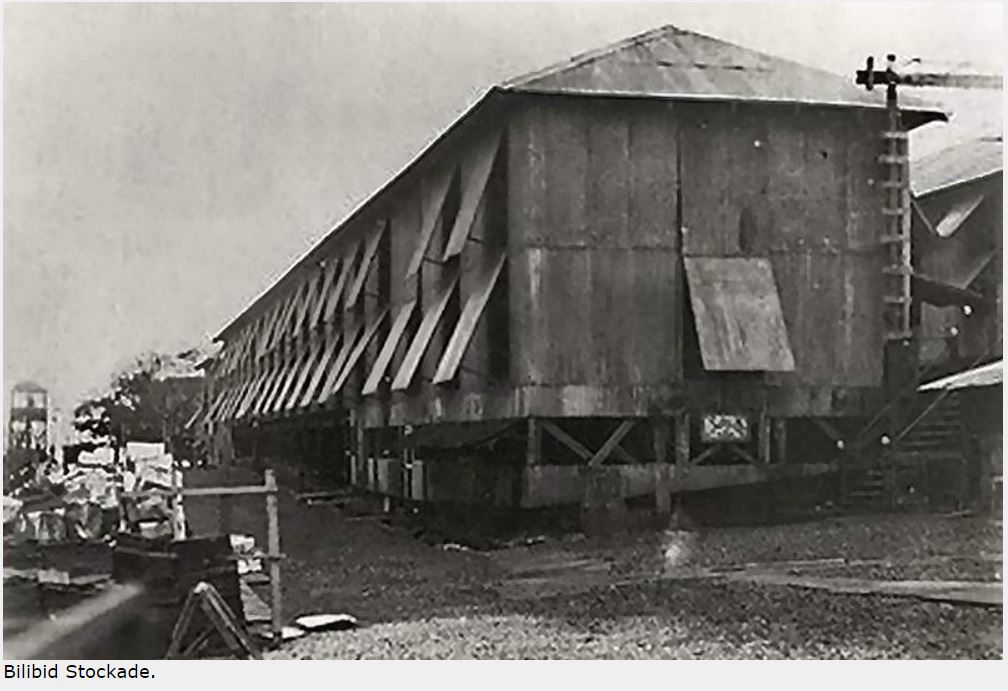

To get the ball rolling, tools, manpower and explosives were necessary. Baguio gold miners provided some advice and old equipment. General Kilbourne negotiated with the Philippine Government for the use of prison labor and hundreds of them were shipped to Corregidor. As long as he fed them, these ‘Bilibids” were his. The barracks area up the hill just west of Bottomside was converted into a secure location for their quarters. The Corregidor 1932 map labels this area as a “Military Stockade”. (Earlier 1921 and 1929 maps do not show a stockade here). Finally, the problem of obtaining explosives turned out to be any easy one to solve. Condemned TNT was located in the US which was gladly shipped to the Philippines.

Zf860. Bilibid prisoners at the Stockade Level.

Zf861. Bilibid prisoners at the Stockade Level

Wouldn’t it be great if we could speak to the man in charge of constructing Malinta tunnel to get the real story? What could be better than that? Well, we don’t need to, he wrote an account of his Corregidor experience and it is available on Corregidor.org. This officer, Lt. Paschal N. Strong of the US Army Corps of Engineers, arrived in the Philippines in 1932 and was promptly put to work. Constructing Malinta Tunnel

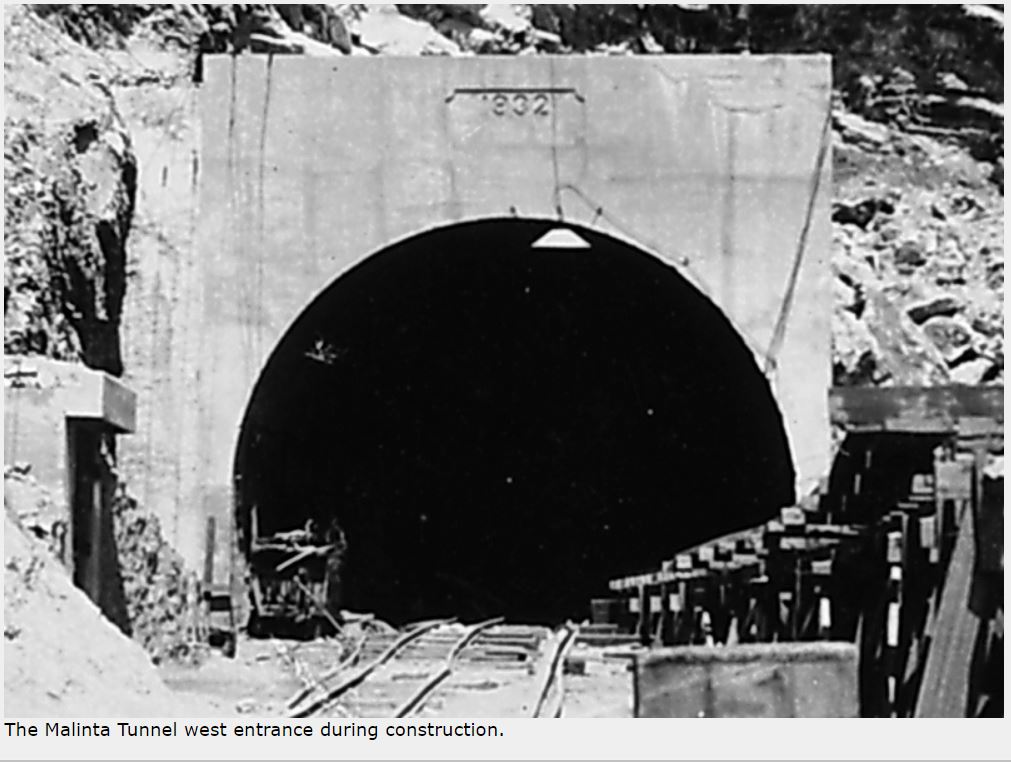

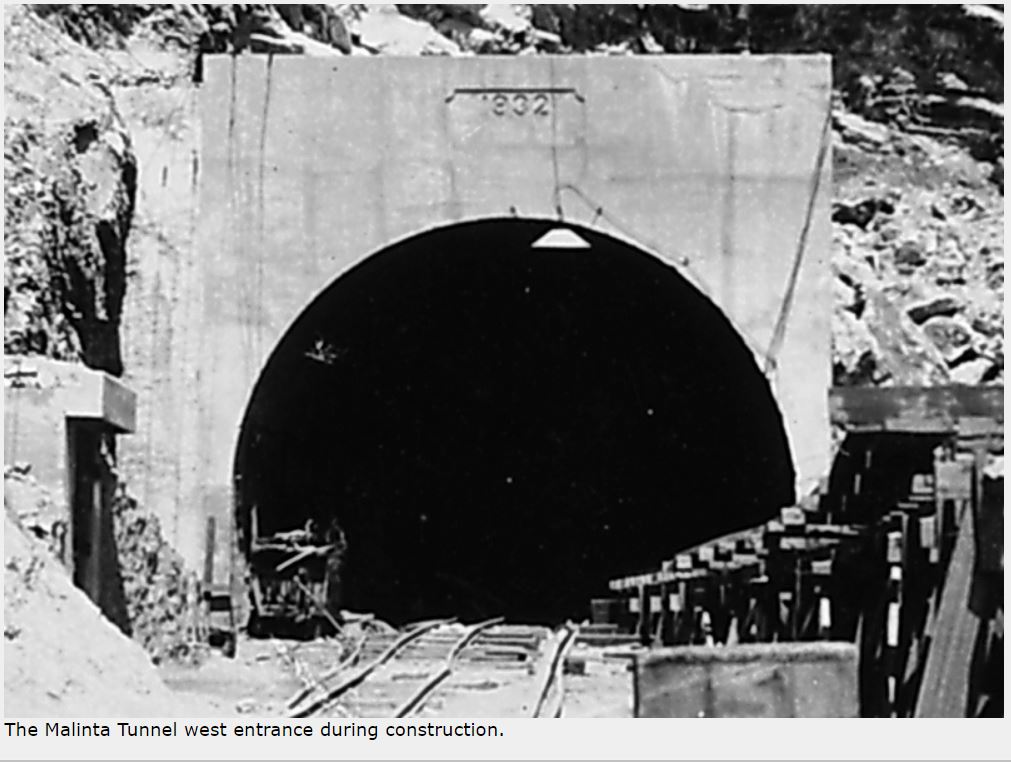

For the 831.6 ft. long main shaft, work commenced simultaneously from both the east and west entrances. This dome shaped shaft had a minimum size of 18 ft. high and 24 ft. wide. Initially the tunnel was unlined. It would also accommodate dual trolley lines. When the two work crews met, the shaft sections lined up within inches of each other. The year was 1932 which was recorded above both tunnel entrances.

The Malinta Tunnel west entrance during construction.

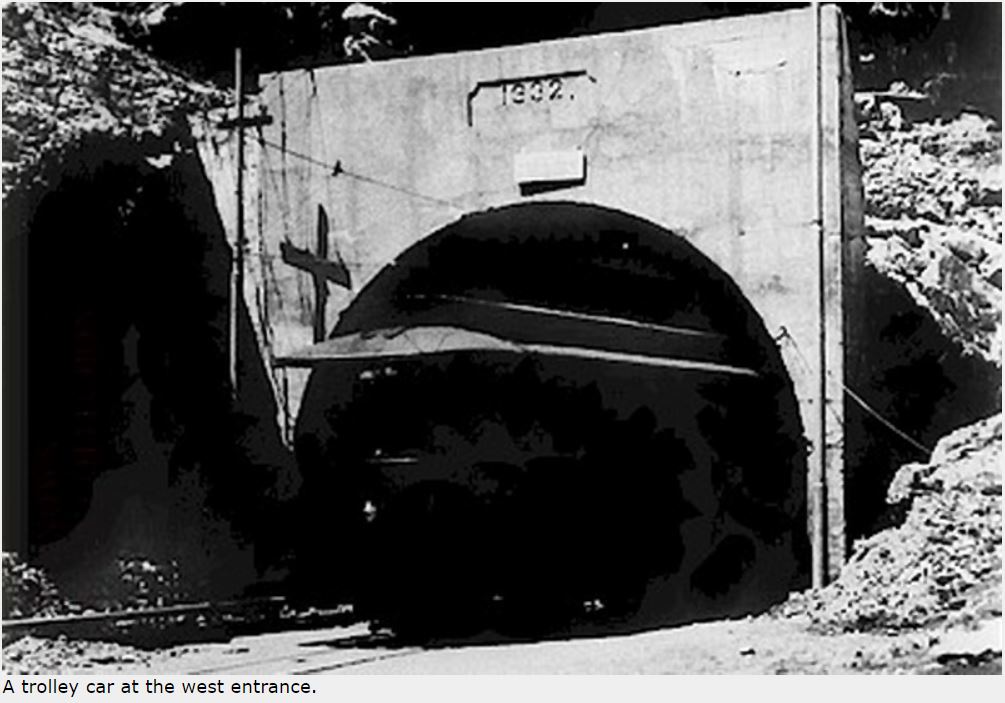

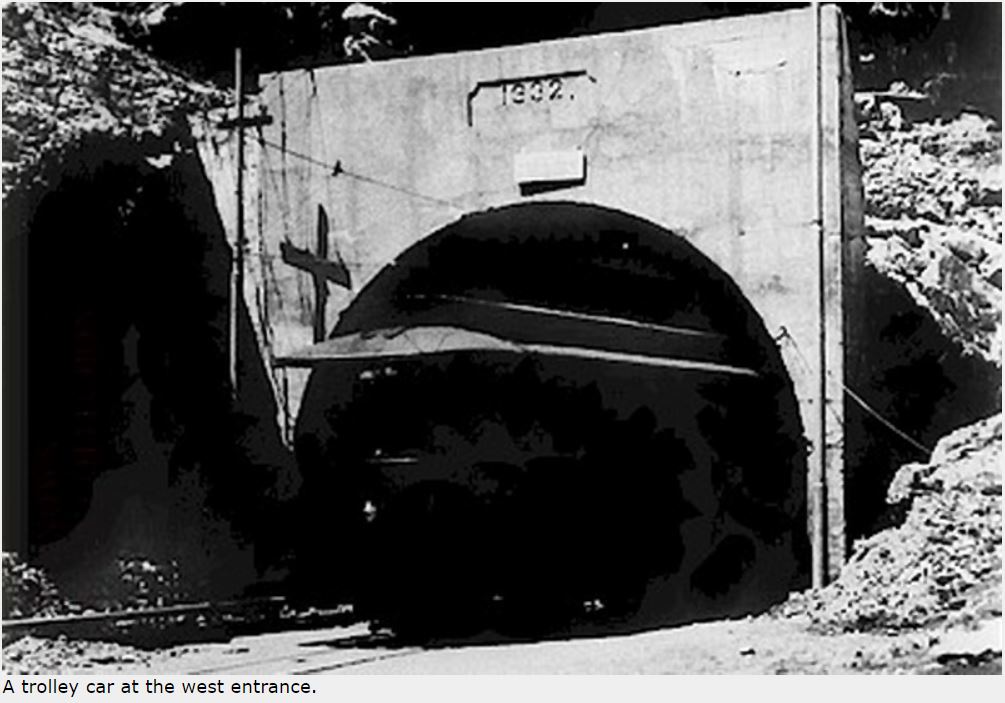

A trolley car at the west entrance.

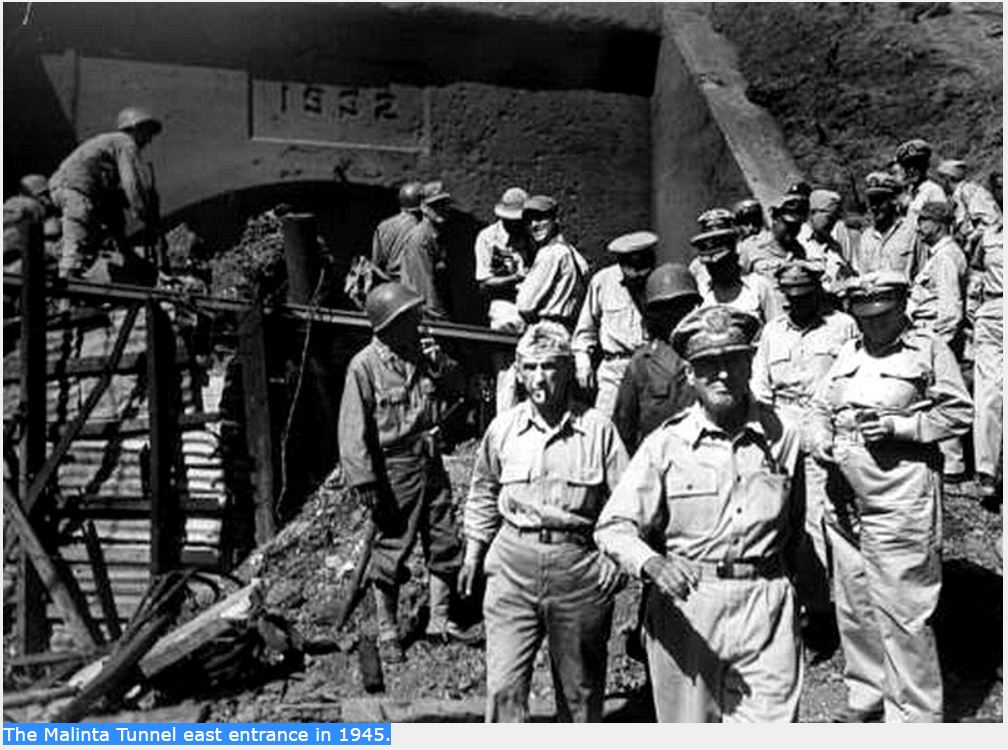

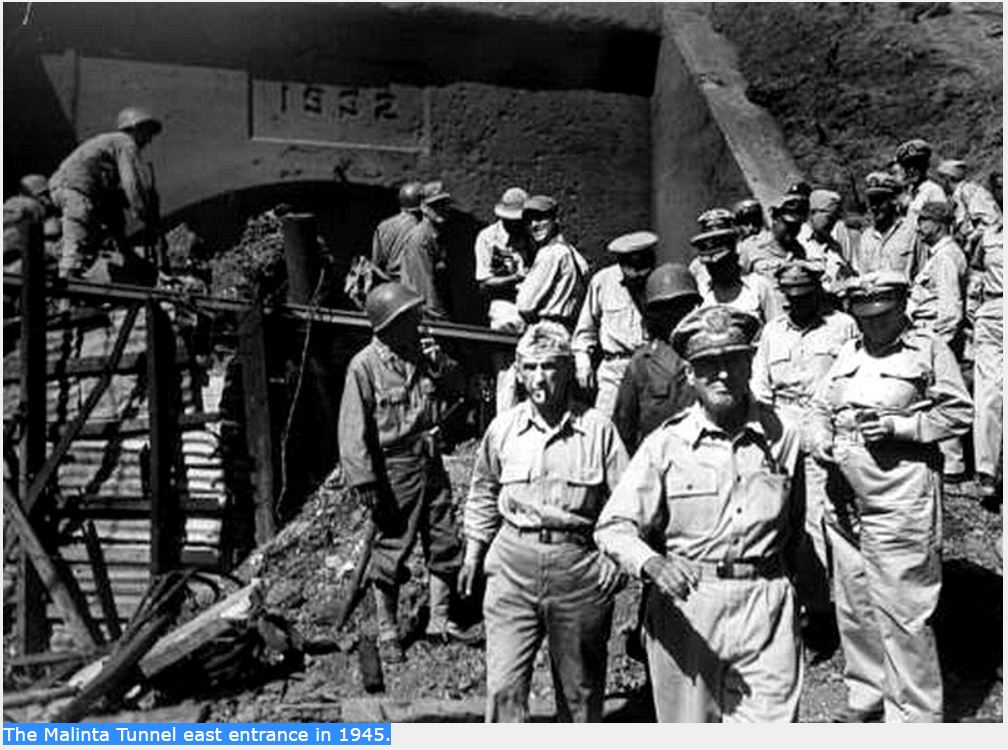

The Malinta Tunnel east entrance in 1945.

The blasting of 24 north and south side laterals was already underway. (22 were for storage facilities as mentioned above and two were passageways to the North and South Systems). Connecting the rear of all laterals were two 4 ft. x 6 ft. ventilation shafts. One air vent from the south side ventilation shaft up to the surface was also constructed.

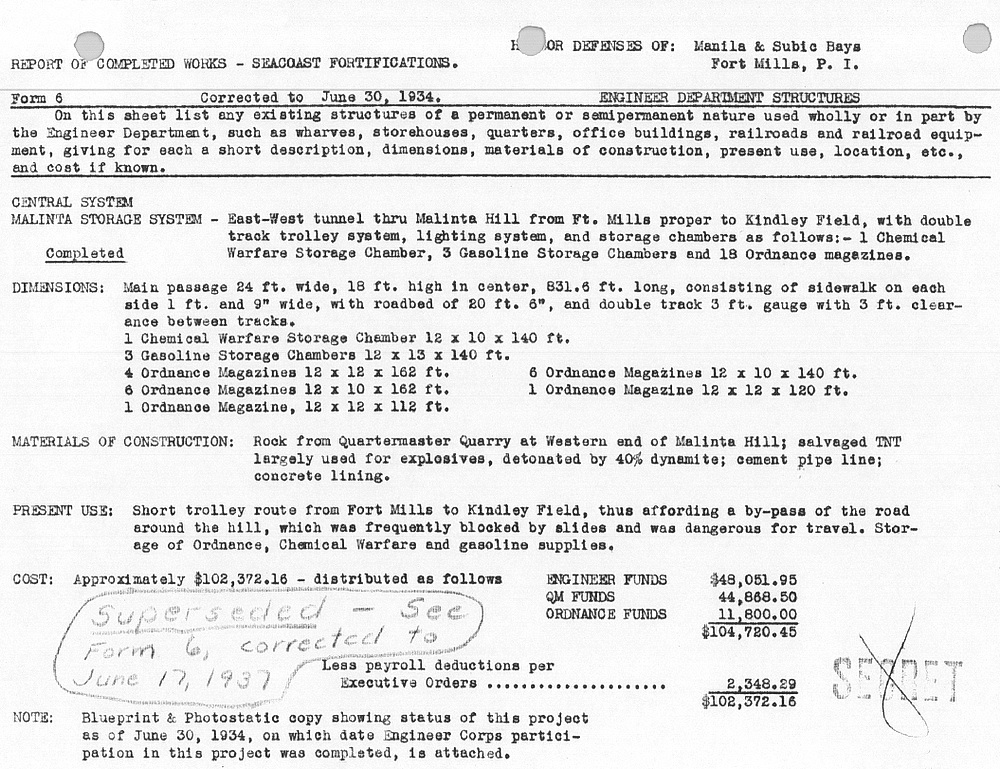

Soon large chunks of flaky rock began falling from the ceiling throughout this unlined tunnel. The new Harbour Defense Commander, Brig. Gen. S D Embick, decided in April of 1933 to line the main shaft and laterals with concrete. He was able to acquire sufficient funds so his staff went shopping. The source that quoted the lowest price including shipping to the Philippines was Japan. On June 30, 1934, the Corps of Engineers issued a Report of Completed Works (RCW) reporting that the central system including the main shaft and adjacent laterals were complete.

Zf865. RCW for the Malinta Central System.

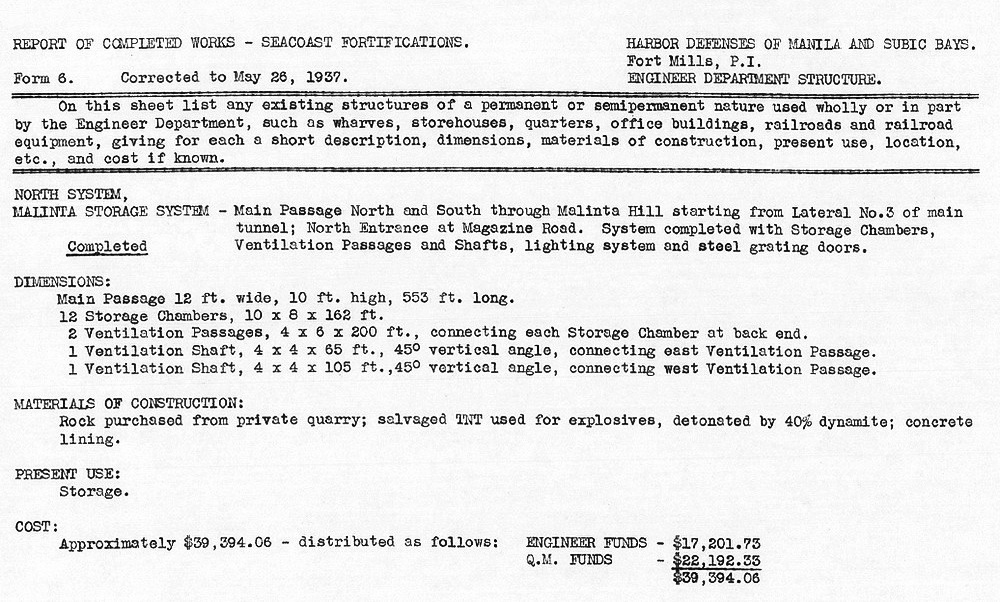

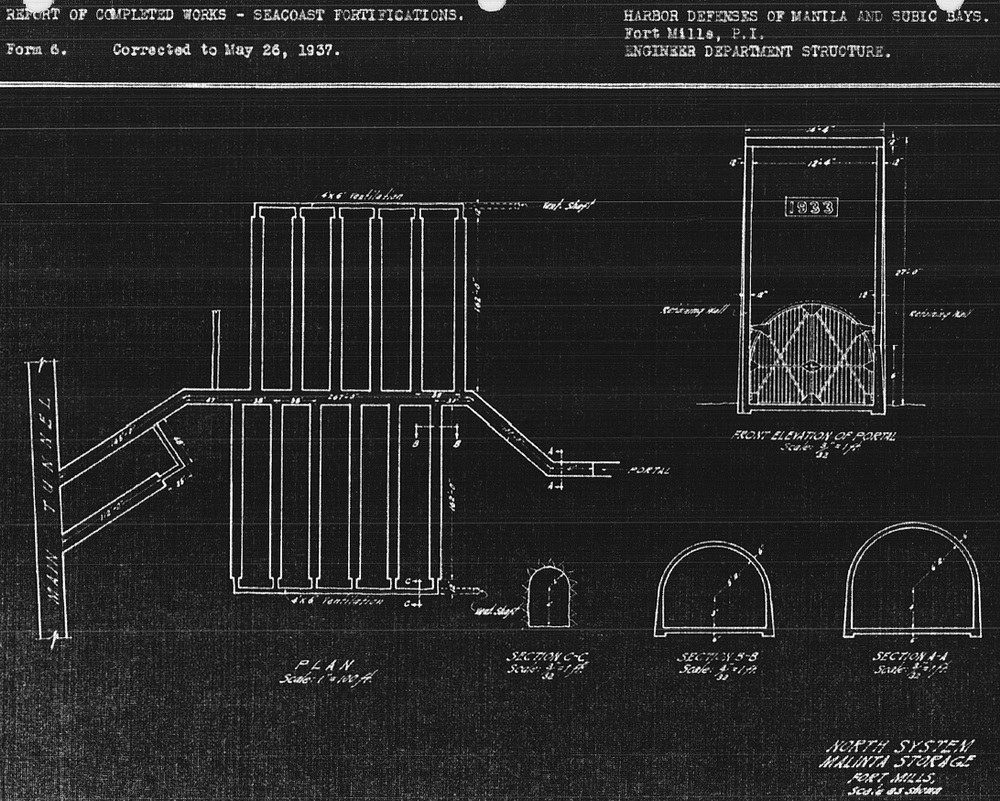

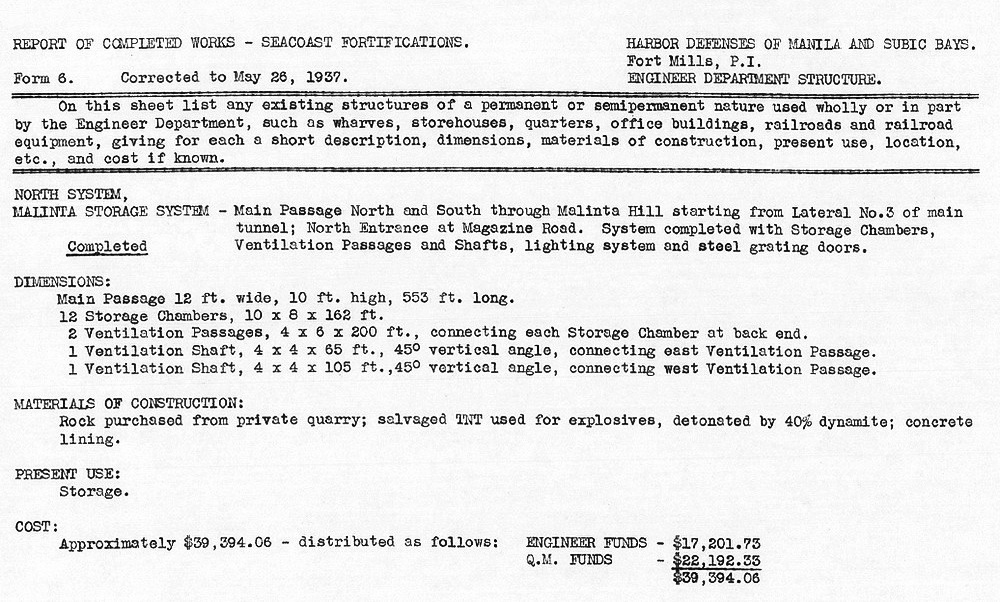

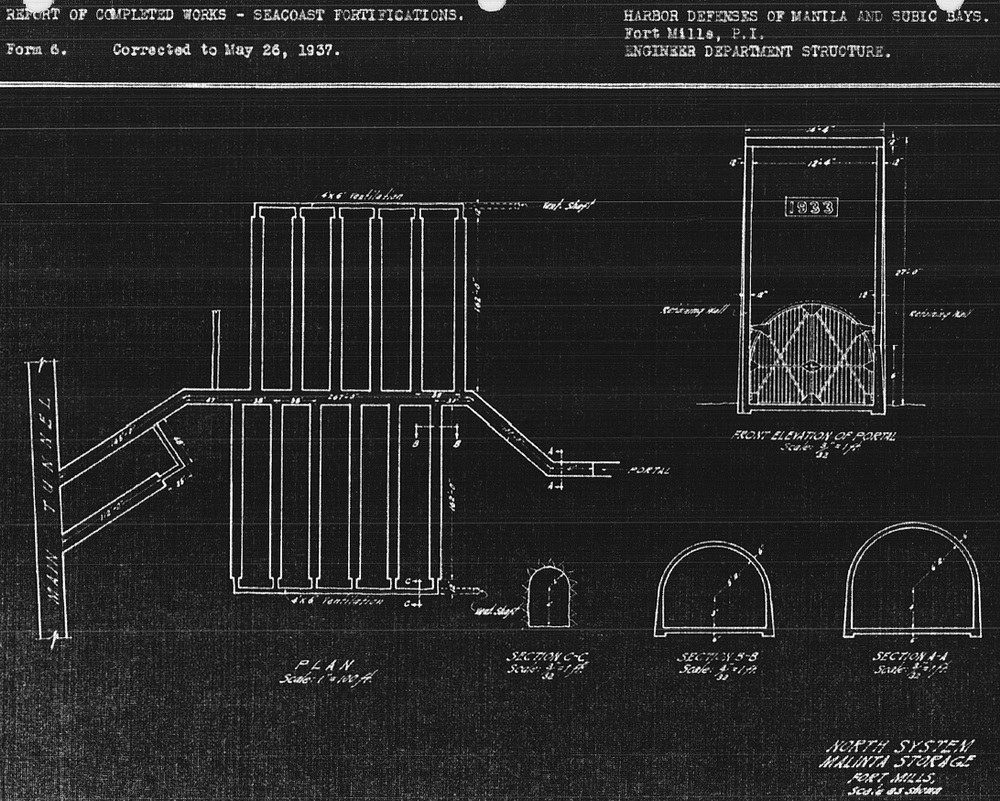

Meanwhile, work was also progressing on the North and South Systems. As of June 30, 1934, the status of the North System was as follows: the main 531 ft. long north-south shaft had been excavated from the Malinta central tunnel to the North Shore Road. Roughly half its length was still a pilot tunnel but the rest was full size. Of the 12 laterals, 10 were partially dug pilot tunnels and the final 2 had yet to be started. Additional work to be completed involved 2 ventilation shafts at the rear of all laterals and 2 exterior ventilation shafts out to the hillside. Only the 12 laterals would be concrete lined. It would be another three years before the North System was reported as complete on May 26, 1937.

Zf866. RCW for the Malinta North System.

Zf867. Blueprint for the Malinta North System.

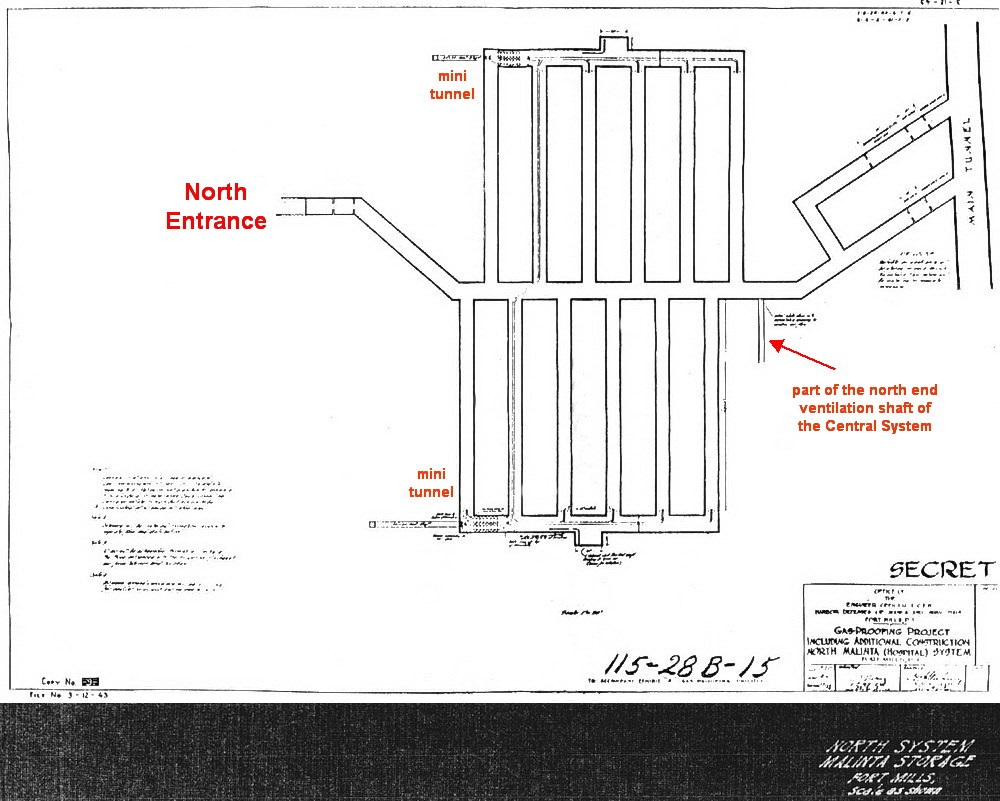

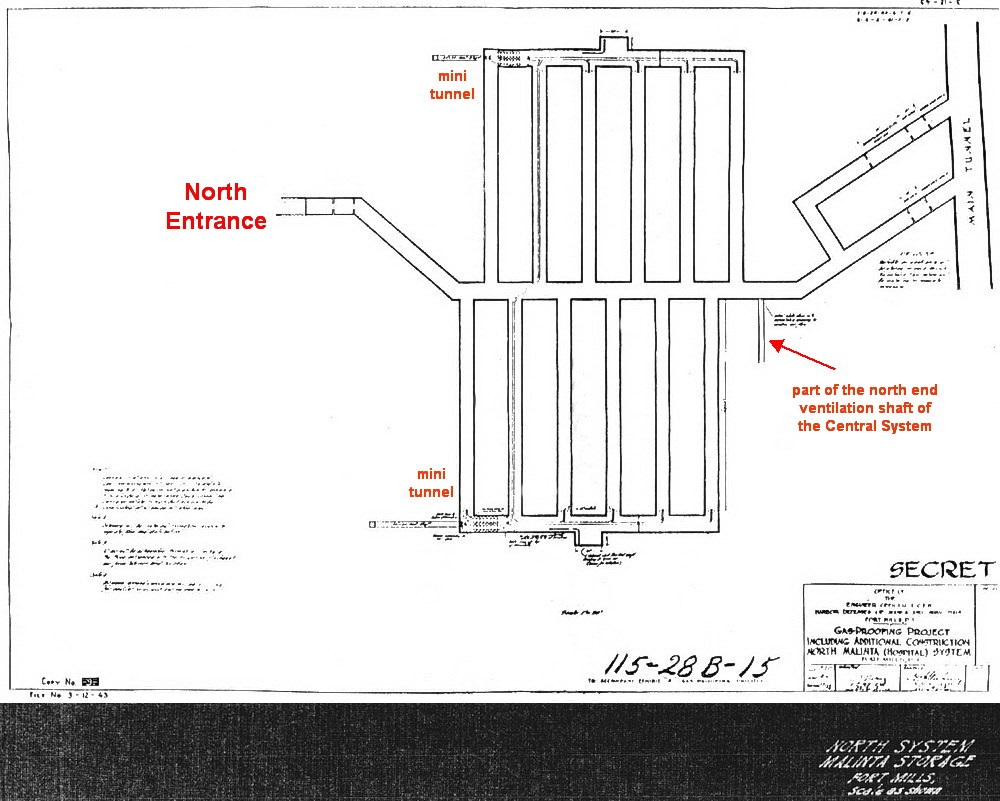

As war approached, the transformation of the North System from the purpose of storage to a hospital took place. According to the book; THE CORPS OF ENGINEERS: THE WAR AGAINST JAPAN, this work was commenced in July of 1941. Major tasks were the enlargement of two rear ventilation shafts beyond their original 4 ft. x 6 ft. sizes plus the addition of water and sewage facilities. Along the floor of both ventilation shafts you can see a drain pipe that runs the full length of them. At the north end of both shafts, horizontal mini tunnels were dug extending the drains to the outside. Today the eastern one is collapsed but the western one still exists. A drain pipe can still be seen embedded in the floor of that small shaft.

Two curious features are present in the hospital. First, both the east and west end ventilation shafts have what appears to be the start of two new laterals that are not shown on early maps. One facing west goes into the rock about fifteen feet or so then stops. The second one facing east ends after only a few feet in a complete collapse.

Second, these tunnel systems were constructed with a slight grade to aid in ventilation and drainage. For example, the Malinta Central System has a grade of 4.08% sloping down towards the west. One hospital lateral near the NW corner has a false floor that is especially noticeable at its western end. This appears to give that lateral the unique feature of having a level floor. Dismissing rumors of hidden treasure, my guess would be that this was the operating theatre where the pooling of blood due to a slanted floor might not be a good thing.

Zf868. Hospital. Unfortunately most of the text on this drawing is unreadable but it clearly shows the outline of the hospital tunnel that we see today. It is labeled “GAS-PROOFING PROJECT INCLUDING ADDITIONAL CONSTRUCTION NORTH MALINTA (HOSPITAL) SYSTEM.” The date of the drawing is not clear.

The South System was to be a much larger complex with a central shaft in excess of 600 feet in length. Storage would be provided by 32 laterals (each 112 ft. long) and there would be an exit out to the SW corner of Malinta Hill. This system was for Quartermaster Corps materials. The status of this system on June 30, 1934 was as follows: a pilot tunnel from the south entrance to 410 ft. along the central shaft had been blasted. Of the 32 laterals, 4 at the south end of the complex were partially completed pilot tunnels; the rest had not yet been started. At the north end of this complex where it joined to the Malinta Central System (at the 3rd lateral from the SW corner), only 15 to 20 feet of tunnel had been blasted.

I cannot determine the exact date but shortly after June of 1934, there was a massive cave-in along the central shaft of this system starting just before Lateral #1 and ending at Lateral #16. The part of Malinta Hill where this system was being constructed had been found to have softer rock than other areas. A decision was made to abandon all work to date (except the south entrance) in favor of relocating the South System further east into more solid rock. The connection point between the South System and the Malinta Central System would now be at Lateral #8 of the main complex.

Slight design changes were implemented in that there would now be 33 laterals. The requirement for a second tunnel entrance would still be met by utilizing the existing south entrance already built at the previous South System location. To accomplish this, a new tunnel to connect the SW entrance to the relocated South System was added.

Work must have progressed quickly as by June 30, 1935, a pilot tunnel over 500 feet long existed from the Malinta Central System (Lateral #8) down to the southern end of the QMC tunnels. From there another pilot tunnel continued west for another 279.4 feet where it intersected the SW tunnel entrance. Also, work on the 4 most northern laterals had been started.

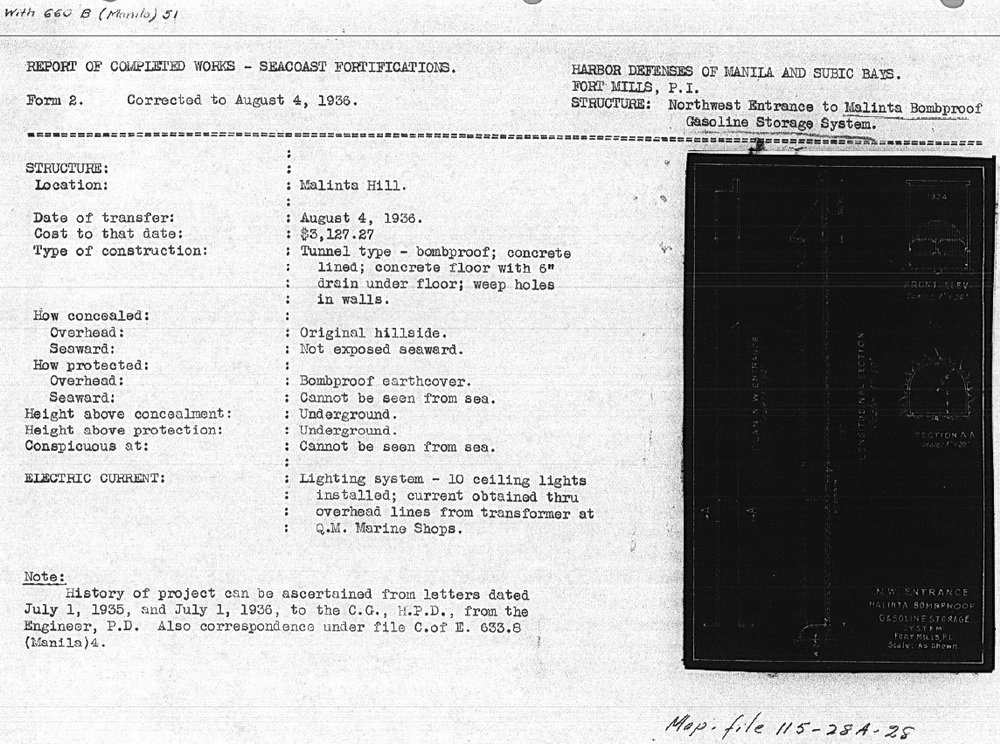

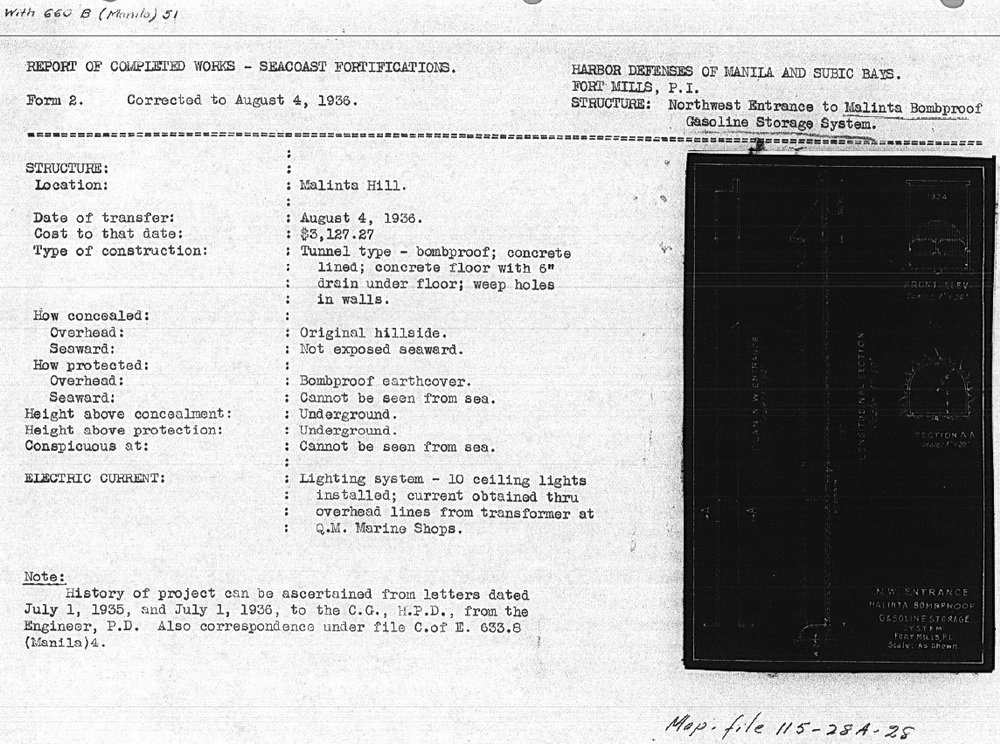

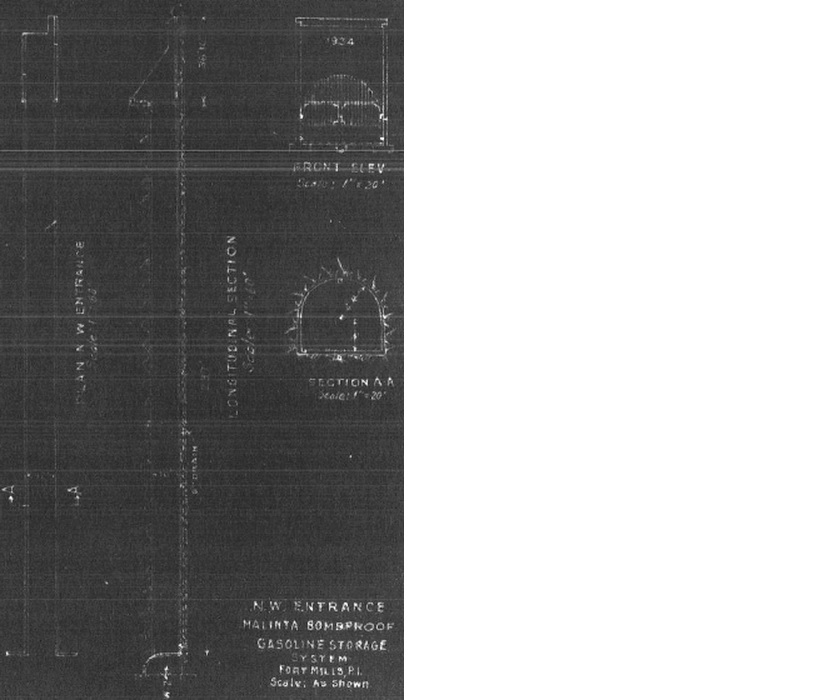

The next area of the Malinta Tunnel complex to be mentioned is known as the Gasoline Tunnel. Located at the NW corner of the Malinta Central System, it consisted of 6 laterals containing large metal storage tanks for gasoline (20 x 8,000 gal. tanks). A central shaft from the laterals ran east-west out to the west side of Malinta Hill. There was one ventilation shaft out to the hillside and with the exception of the rear ventilation shaft, the tunnel system was fully concrete lined. The 1934 map shows the Gasoline Tunnel to exist at that time but it must have been incomplete. Above the tunnel’s concrete entrance was a date of 1934 but the RCW released by the Corps of Engineers was not issued until August 4 of 1936.

Zf869. RCW for the Malinta Gasoline Tunnel.

Zf870. Enlargement of the RCW Malinta Gasoline Tunnel blueprint.

The RCWs indicate when construction of all sections of Malinta Tunnel were completed with the exception of the South System. I have no RCW for it. Is this simply because (1) I do not have that document, (2) it is lost in some archive or (3) it never got issued by the Corps of Engineers. Additional construction was obviously completed and there may have been periods of inactivity but I know that work continued in the South System even up until wartime. Reason #3 may be correct in that work never really ceased here. The last detailed map that I am aware of is dated July 2, 1940. As of that date, eleven South System laterals were partially complete.

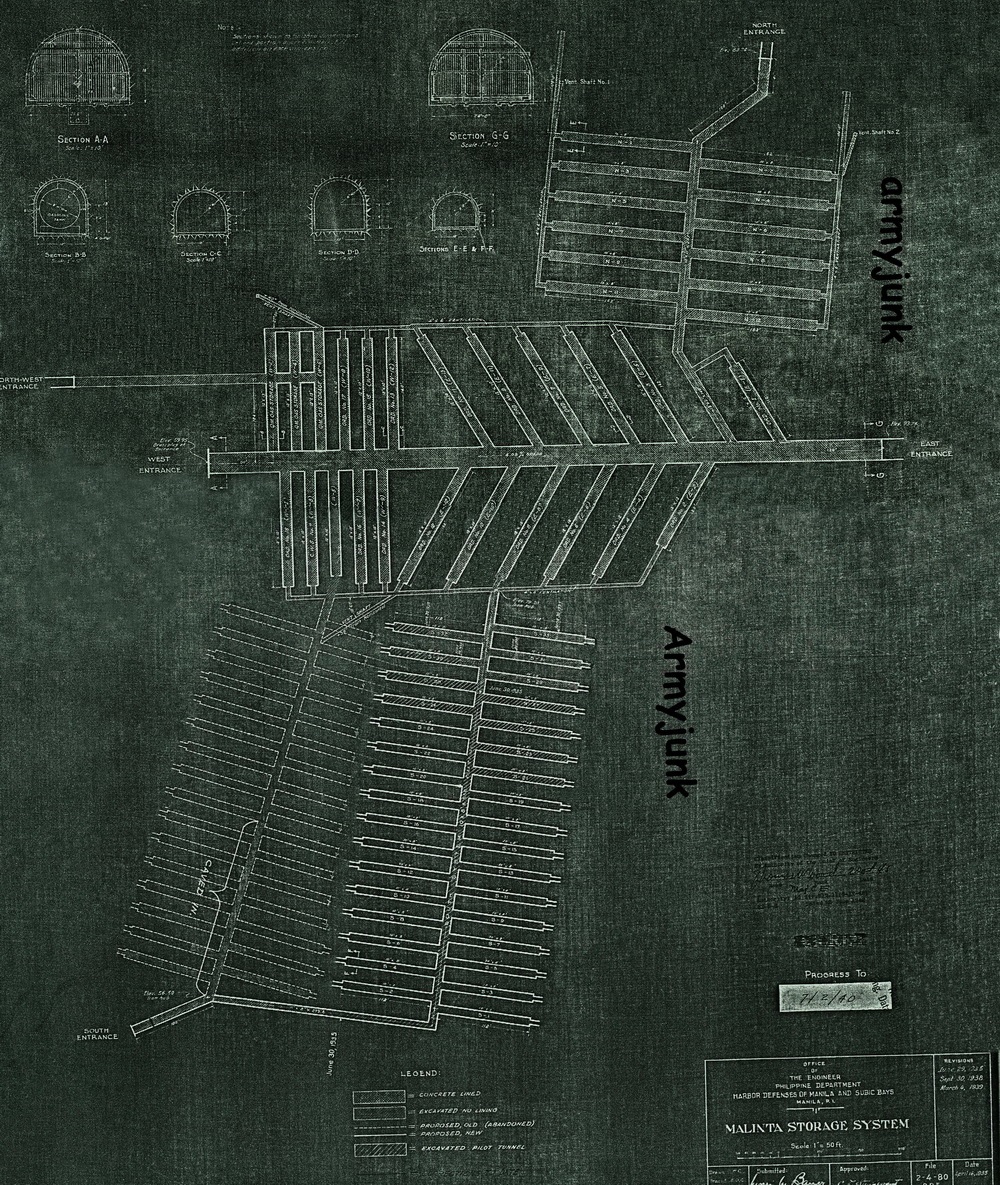

Zf871. This detailed map dated July 2, 1940 is interesting as it overlays the old and new location of the South System and gives an overall view of the whole complex. (map courtesy of armyjunk).

Fears of an upcoming war would soon bring the US Navy into the picture adding some confusion as to who controlled what SW tunnel space. The Navy expected to lose Cavite’s base facilities when war came so in 1939 it released funds to the Army Engineers. They were to drive 4 tunnels into the south-west side of Malinta Hill and be connected by a shaft to the Army’s South Tunnel Complex. (info from ‘Corregidor, The Saga of a Fortress’ by the Belote Brothers). These tunnels would become HQ of the 16th Naval District.

The Navy tunnels initiative had little effect on the Army’s Malinta Tunnel system with one possible exception; did the QMC South System lose its southern entrance to the Navy? What we believe to be tunnel Queen does connect to the shaft heading to the south entrance. Whether due to secrecy or inter-service rivalry, can you imagine Army personnel wandering through secure Navy tunnel areas to get to the south entrance? I doubt it. Unfortunately, details of the secret Navy tunnels are scarce. Even today I know of no Navy or Army Corps of Engineer blueprints for them.

A discussion of the Malinta Navy tunnels is located here: Malinta Navy Tunnels

The possible loss of the SW Malinta entrance to the Navy may be one reason for the construction of a new entrance from the QMC South System out to the South Shore Road. This road passes along the south side of Malinta Hill between Bottomside and Tailside. Another reason could have been the QMC’s need for a relatively straight tunnel which would allow for easy transport of materials to and from the storage laterals. The entrance is angled towards Bottomside which would have helped in the moving of longer items such as torpedoes in and out of the QMC tunnels. When this work was undertaken seems to be unknown but would have been started after July of 1940.

In 1941 with war approaching, Washington’s purse strings were starting to get loosened and long delayed projects found approval. One such project was for the gas-proofing of Malinta Tunnel. Over a half million dollars was allocated for this however very little material arrived before the start of the war. According to the book “THE CHEMICAL WARFARE SERVICE: CHEMICALS IN COMBAT”, the only portion of this project to get completed was the installation of blowers for ventilation.

If you omit the missing ‘new’ south entrance and the Hospital mini tunnels (and a few other minor details) then the 1940 blueprint is an accurate depiction of the Malinta Tunnel we know today.

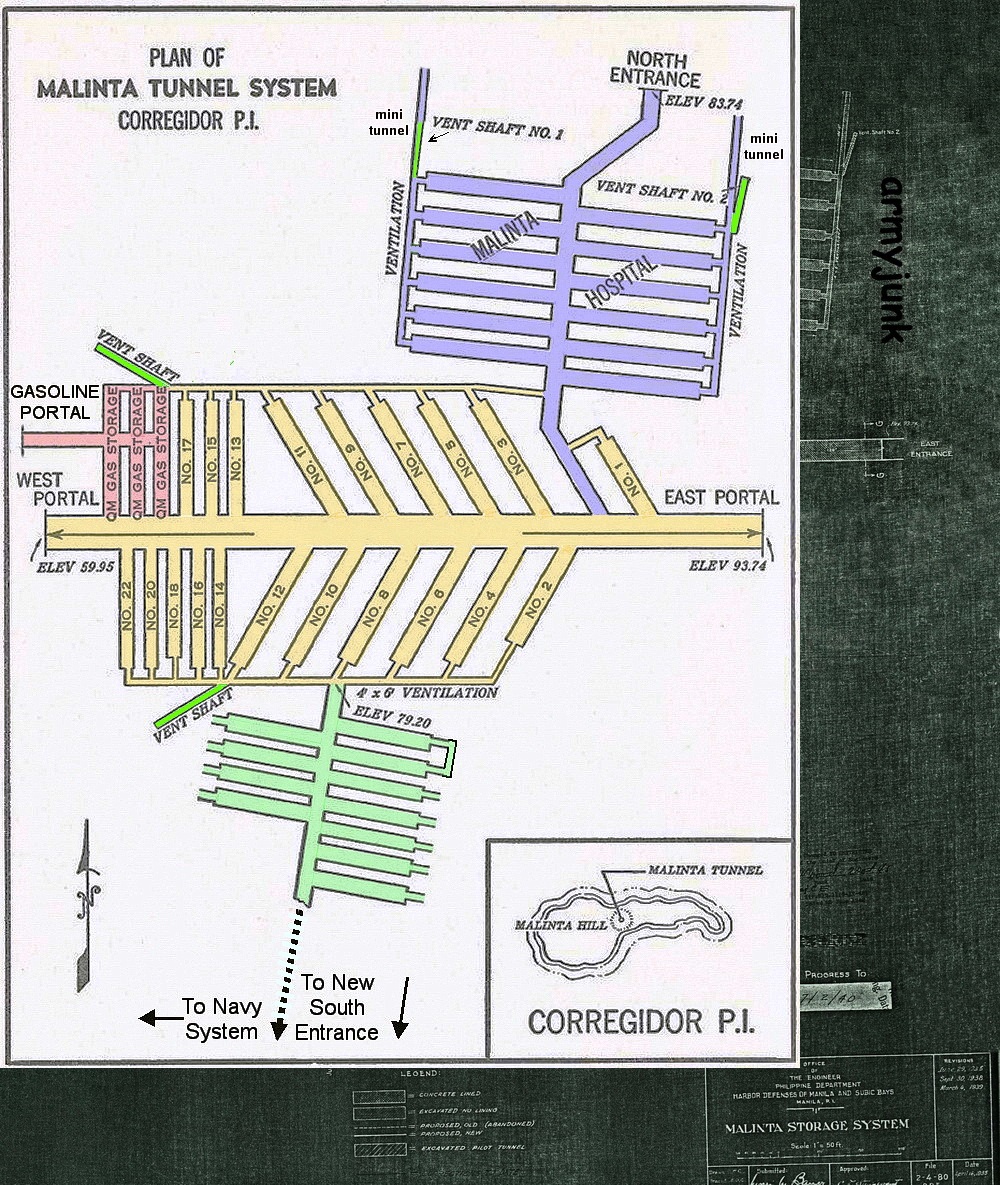

Zf872. The above map is a good overview of the Malinta Tunnel System. There are minor errors but it is generally correct. (Modified map from ‘The Hard Way Home’ by Col. William C. Braly)

In the spring of 1941, Maj. Gen. George F. Moore became the Harbour Defense Commander. It was under his watch that Malinta Tunnel would be put to the use that it was intended for twenty years earlier. Probably the most fitting tribute to this tunnel complex came from him when he said “Without the shelter afforded by the Malinta Tunnel…organized defense of the Philippines would have collapsed in its early stages”.

For me, Malinta Tunnel will always be one of the most interesting places to visit on Corregidor Island. Stories of hidden gold and ghosts have nothing to do with it. I should note that the information written above speaks only of cavities carved into the rock; there is no mention of the few thousand people who either temporarily lived here or who died within these passageways. History is the real attraction and it lurks everywhere you step.

While trying to research this subject, I encountered the usual cases of disagreeing information so what I present here is a summary based on what I understand to be correct. I consider the most reliable information to come from the US Army’s ‘Corps of Engineers’. This includes correspondence, official blueprints and Records of Completed Works. These are factual records recorded by Army Engineers as the work progressed. Various books were a secondary source.

By far the biggest (and widely accepted) misconceptions are the tunnel construction dates. Numerous internet searches plus books and articles state that the Malinta Tunnel was built during the ten year period between 1922 and 1932. These dates are also quoted daily to tourists who visit the island. I can see where this idea may have come from though. One of the tunnel entrances has these dates stenciled on it. The source of this information is unknown.

Zf857. 1966 photo of the Malinta Tunnel North entrance with the wrong stenciled construction timeline information

A photo of the same partially repainted entrance taken two years ago.[/span]

Inaccurate history has become accepted history! I have learned that absolutely no construction took place during this period. For this project, not a single rock was disturbed on Malinta Hill. The correct period starts later in 1932 and continues in several phases up to and including wartime.

Part 1: The Malinta Tunnel from Concept to Completion

Post WWI, the Army realized that Corregidor’s fortifications and defenses were inadequate should a future war break out. This prompted the creation of elaborate plans to rectify these concerns. Two items topping the list were additional storage which was to be bombproof and protection from potential Japanese gas attacks; the idea for a large tunnel under Malinta Hill was born. Driven by Fort Mills commander, Brig. Gen Richmond P. Davis, the Quartermaster Corps drafted a proposal. Here are excerpts from that document.

May 26, 1921

From: Quarter Master Corps Office, Head Quarters, Philippines.

To: Colonel Eltinge,

Subject: Malinta Hill Tunnel proposed for Fort Mills.

Paragraph No.1 mentions:

In the Annual Estimate from Fort Mills, recently submitted, there was included a proposition to tunnel Malinta Hill and provide bomb proof storeroom leading from this tunnel. The entrance to the tunnel would be in the neighborhood of the present rock crushing plant and would extend through under the hill to connect with the tactical road leading to Kindley Field (the new Air Service project) and to the defenses on the tail of the island. It is proposed to make the tunnel about 650 feet long, 16 feet wide and 19 feet high. The roof will be arched. The tunnel would have concrete walls, roof and floor. The tunnel would be placed on a grade so that natural ventilation would result.

1) A single trolley line is planned for the original installation but space is provided so that a double track may be installed later. Four storerooms are to lead from this tunnel, each storeroom to be 40 feet by 80 feet in the clear with an arched roof and concrete lining. Lighting, drainage, and ventilation would be provided for these rooms as well as light for the tunnel.

2) The bomb-proof storerooms would be invaluable in time of war and the tunnel could be used as an emergency hospital. There is no bomb-proof storage for supplies available, and Malinta Hill is the logical place for such a base. This hill is ideal for bomb-proof storerooms and magazines. It is adjacent to the terminal and in time of war could be entirely honeycombed with underground storerooms.

3) The present road around Malinta Hill that furnishes the only good road to Kindley Field and the tail of the island is so situated as to be easily rendered useless by a shell striking any part of the South slope of the hill. Further, this road is exposed to the open sea and is likely to receive shell fire from long-range guns of ships making an attack.

4) The post people state further that the rock taken from this tunnel would be utilized in the repair and maintenance of Post Utilities. There would thus be a slight saving in the construction because it would not be necessary to dispose of the material excavated.

5) The estimated cost of this work is $650,000.00. It is understood that this estimate was carefully prepared by the post authorities and no doubt is approximately correct. Some changes may be necessary in the sizes of the rooms that will result in a slight change of the estimated cost.

6) The arguments for this storehouse are essentially tactical. The reasons become apparent when a study of the storage facilities of the entire island is made. There is no question that additional storage must be provided generally, and it appears that it would be more logical to make bomb-proof space at somewhat additional costs than to place storehouses in the open that are likely to be destroyed during hostilities at the time supplies will be needed.

W. A. Danielson

Assistant Quartermaster

Unknown to General Davis, an event on the other side of the world would soon derail his tunnel plans. Due to fears of a naval arms race in the lean post WWI years, a conference would soon be held in Washington. The five primary naval powers (USA, Great Britain, Japan, France and Italy) attended along with observers from several other countries. The conference started in November of 1921 and concluded with the signing of a treaty in February of 1922.

You may be wondering, what does a naval ship limitation treaty have to do with an Army fort called Corregidor? Well, it appears that the Japanese were reluctant to sign the treaty so the US offered them an incentive. The result was Article XIX which was in effect, a Non-Fortification Clause. It stated that there would be no strengthening of American seacoast installations beyond the 180th parallel of latitude. (i.e. west of Midway Island). Any new armament or defensive improvements to Corregidor were “on hold” until the treaty expired on December 31st, 1937. The Malinta Tunnel project was halted.

A positive turn of events occurred when Brig. Gen. Charles E. Kilbourne assumed command of Harbour Defense in 1929. With very limited funds he began a series of work projects to improve Corregidor. Roads were widened, trees planted, barracks upgraded and Topside got a new swimming pool adjacent to the Officer’s Club. One tunnel near Battery Wheeler was also completed but this work was kept quiet.

In December of 1931, Kilbourne revived the idea of a tunnel under Malinta Hill. Although he had much wider ranging plans than were originally proposed, he only told his superiors he would build a tunnel through the hill to extend the streetcar line towards Kindley Field. Since the North and South Shore roads around Malinta Hill were dangerous due to rock fall then this would save lives. He would not require funds from Washington and tunnel rock would be crushed and used elsewhere on the island lowering future maintenance costs. If anyone in the US knew the details of what Kilbourne was doing then it was kept secret. Washington approved the tunnel project and final plans were initialed by Kilbourne on January 14th, 1932.

The initial 1921 requirement of four underground storerooms was abandoned and a much more elaborate complex was designed. It would allow for bomb-proof storage of ammunition and supplies in addition to being a gas-proof shelter. In wartime it could also function as a hospital and HQ. (Note that this gas-proofing was never completed). The allocation of central system storage laterals would be; 1 for Chemical Warfare, 3 for Gasoline and 18 for Ordnance.

Along with the central system laterals, north and south systems would also be constructed. The North System would have 12 storage laterals and the South System for the QMC would have 32 laterals. In addition to being connected to the central system, both the North and South systems would have a second entrance.

Zf859 Malinta Tunnel System map dated 1934 showing the overall design and construction to date.

To get the ball rolling, tools, manpower and explosives were necessary. Baguio gold miners provided some advice and old equipment. General Kilbourne negotiated with the Philippine Government for the use of prison labor and hundreds of them were shipped to Corregidor. As long as he fed them, these ‘Bilibids” were his. The barracks area up the hill just west of Bottomside was converted into a secure location for their quarters. The Corregidor 1932 map labels this area as a “Military Stockade”. (Earlier 1921 and 1929 maps do not show a stockade here). Finally, the problem of obtaining explosives turned out to be any easy one to solve. Condemned TNT was located in the US which was gladly shipped to the Philippines.

Zf860. Bilibid prisoners at the Stockade Level.

Zf861. Bilibid prisoners at the Stockade Level

Wouldn’t it be great if we could speak to the man in charge of constructing Malinta tunnel to get the real story? What could be better than that? Well, we don’t need to, he wrote an account of his Corregidor experience and it is available on Corregidor.org. This officer, Lt. Paschal N. Strong of the US Army Corps of Engineers, arrived in the Philippines in 1932 and was promptly put to work. Constructing Malinta Tunnel

For the 831.6 ft. long main shaft, work commenced simultaneously from both the east and west entrances. This dome shaped shaft had a minimum size of 18 ft. high and 24 ft. wide. Initially the tunnel was unlined. It would also accommodate dual trolley lines. When the two work crews met, the shaft sections lined up within inches of each other. The year was 1932 which was recorded above both tunnel entrances.

The Malinta Tunnel west entrance during construction.

A trolley car at the west entrance.

The Malinta Tunnel east entrance in 1945.

The blasting of 24 north and south side laterals was already underway. (22 were for storage facilities as mentioned above and two were passageways to the North and South Systems). Connecting the rear of all laterals were two 4 ft. x 6 ft. ventilation shafts. One air vent from the south side ventilation shaft up to the surface was also constructed.

Soon large chunks of flaky rock began falling from the ceiling throughout this unlined tunnel. The new Harbour Defense Commander, Brig. Gen. S D Embick, decided in April of 1933 to line the main shaft and laterals with concrete. He was able to acquire sufficient funds so his staff went shopping. The source that quoted the lowest price including shipping to the Philippines was Japan. On June 30, 1934, the Corps of Engineers issued a Report of Completed Works (RCW) reporting that the central system including the main shaft and adjacent laterals were complete.

Zf865. RCW for the Malinta Central System.

Meanwhile, work was also progressing on the North and South Systems. As of June 30, 1934, the status of the North System was as follows: the main 531 ft. long north-south shaft had been excavated from the Malinta central tunnel to the North Shore Road. Roughly half its length was still a pilot tunnel but the rest was full size. Of the 12 laterals, 10 were partially dug pilot tunnels and the final 2 had yet to be started. Additional work to be completed involved 2 ventilation shafts at the rear of all laterals and 2 exterior ventilation shafts out to the hillside. Only the 12 laterals would be concrete lined. It would be another three years before the North System was reported as complete on May 26, 1937.

Zf866. RCW for the Malinta North System.

Zf867. Blueprint for the Malinta North System.

As war approached, the transformation of the North System from the purpose of storage to a hospital took place. According to the book; THE CORPS OF ENGINEERS: THE WAR AGAINST JAPAN, this work was commenced in July of 1941. Major tasks were the enlargement of two rear ventilation shafts beyond their original 4 ft. x 6 ft. sizes plus the addition of water and sewage facilities. Along the floor of both ventilation shafts you can see a drain pipe that runs the full length of them. At the north end of both shafts, horizontal mini tunnels were dug extending the drains to the outside. Today the eastern one is collapsed but the western one still exists. A drain pipe can still be seen embedded in the floor of that small shaft.

Two curious features are present in the hospital. First, both the east and west end ventilation shafts have what appears to be the start of two new laterals that are not shown on early maps. One facing west goes into the rock about fifteen feet or so then stops. The second one facing east ends after only a few feet in a complete collapse.

Second, these tunnel systems were constructed with a slight grade to aid in ventilation and drainage. For example, the Malinta Central System has a grade of 4.08% sloping down towards the west. One hospital lateral near the NW corner has a false floor that is especially noticeable at its western end. This appears to give that lateral the unique feature of having a level floor. Dismissing rumors of hidden treasure, my guess would be that this was the operating theatre where the pooling of blood due to a slanted floor might not be a good thing.

Zf868. Hospital. Unfortunately most of the text on this drawing is unreadable but it clearly shows the outline of the hospital tunnel that we see today. It is labeled “GAS-PROOFING PROJECT INCLUDING ADDITIONAL CONSTRUCTION NORTH MALINTA (HOSPITAL) SYSTEM.” The date of the drawing is not clear.

The South System was to be a much larger complex with a central shaft in excess of 600 feet in length. Storage would be provided by 32 laterals (each 112 ft. long) and there would be an exit out to the SW corner of Malinta Hill. This system was for Quartermaster Corps materials. The status of this system on June 30, 1934 was as follows: a pilot tunnel from the south entrance to 410 ft. along the central shaft had been blasted. Of the 32 laterals, 4 at the south end of the complex were partially completed pilot tunnels; the rest had not yet been started. At the north end of this complex where it joined to the Malinta Central System (at the 3rd lateral from the SW corner), only 15 to 20 feet of tunnel had been blasted.

I cannot determine the exact date but shortly after June of 1934, there was a massive cave-in along the central shaft of this system starting just before Lateral #1 and ending at Lateral #16. The part of Malinta Hill where this system was being constructed had been found to have softer rock than other areas. A decision was made to abandon all work to date (except the south entrance) in favor of relocating the South System further east into more solid rock. The connection point between the South System and the Malinta Central System would now be at Lateral #8 of the main complex.

Slight design changes were implemented in that there would now be 33 laterals. The requirement for a second tunnel entrance would still be met by utilizing the existing south entrance already built at the previous South System location. To accomplish this, a new tunnel to connect the SW entrance to the relocated South System was added.

Work must have progressed quickly as by June 30, 1935, a pilot tunnel over 500 feet long existed from the Malinta Central System (Lateral #8) down to the southern end of the QMC tunnels. From there another pilot tunnel continued west for another 279.4 feet where it intersected the SW tunnel entrance. Also, work on the 4 most northern laterals had been started.

The next area of the Malinta Tunnel complex to be mentioned is known as the Gasoline Tunnel. Located at the NW corner of the Malinta Central System, it consisted of 6 laterals containing large metal storage tanks for gasoline (20 x 8,000 gal. tanks). A central shaft from the laterals ran east-west out to the west side of Malinta Hill. There was one ventilation shaft out to the hillside and with the exception of the rear ventilation shaft, the tunnel system was fully concrete lined. The 1934 map shows the Gasoline Tunnel to exist at that time but it must have been incomplete. Above the tunnel’s concrete entrance was a date of 1934 but the RCW released by the Corps of Engineers was not issued until August 4 of 1936.

Zf869. RCW for the Malinta Gasoline Tunnel.

Zf870. Enlargement of the RCW Malinta Gasoline Tunnel blueprint.

The RCWs indicate when construction of all sections of Malinta Tunnel were completed with the exception of the South System. I have no RCW for it. Is this simply because (1) I do not have that document, (2) it is lost in some archive or (3) it never got issued by the Corps of Engineers. Additional construction was obviously completed and there may have been periods of inactivity but I know that work continued in the South System even up until wartime. Reason #3 may be correct in that work never really ceased here. The last detailed map that I am aware of is dated July 2, 1940. As of that date, eleven South System laterals were partially complete.

Zf871. This detailed map dated July 2, 1940 is interesting as it overlays the old and new location of the South System and gives an overall view of the whole complex. (map courtesy of armyjunk).

Fears of an upcoming war would soon bring the US Navy into the picture adding some confusion as to who controlled what SW tunnel space. The Navy expected to lose Cavite’s base facilities when war came so in 1939 it released funds to the Army Engineers. They were to drive 4 tunnels into the south-west side of Malinta Hill and be connected by a shaft to the Army’s South Tunnel Complex. (info from ‘Corregidor, The Saga of a Fortress’ by the Belote Brothers). These tunnels would become HQ of the 16th Naval District.

The Navy tunnels initiative had little effect on the Army’s Malinta Tunnel system with one possible exception; did the QMC South System lose its southern entrance to the Navy? What we believe to be tunnel Queen does connect to the shaft heading to the south entrance. Whether due to secrecy or inter-service rivalry, can you imagine Army personnel wandering through secure Navy tunnel areas to get to the south entrance? I doubt it. Unfortunately, details of the secret Navy tunnels are scarce. Even today I know of no Navy or Army Corps of Engineer blueprints for them.

A discussion of the Malinta Navy tunnels is located here: Malinta Navy Tunnels

The possible loss of the SW Malinta entrance to the Navy may be one reason for the construction of a new entrance from the QMC South System out to the South Shore Road. This road passes along the south side of Malinta Hill between Bottomside and Tailside. Another reason could have been the QMC’s need for a relatively straight tunnel which would allow for easy transport of materials to and from the storage laterals. The entrance is angled towards Bottomside which would have helped in the moving of longer items such as torpedoes in and out of the QMC tunnels. When this work was undertaken seems to be unknown but would have been started after July of 1940.

In 1941 with war approaching, Washington’s purse strings were starting to get loosened and long delayed projects found approval. One such project was for the gas-proofing of Malinta Tunnel. Over a half million dollars was allocated for this however very little material arrived before the start of the war. According to the book “THE CHEMICAL WARFARE SERVICE: CHEMICALS IN COMBAT”, the only portion of this project to get completed was the installation of blowers for ventilation.

If you omit the missing ‘new’ south entrance and the Hospital mini tunnels (and a few other minor details) then the 1940 blueprint is an accurate depiction of the Malinta Tunnel we know today.

Zf872. The above map is a good overview of the Malinta Tunnel System. There are minor errors but it is generally correct. (Modified map from ‘The Hard Way Home’ by Col. William C. Braly)

In the spring of 1941, Maj. Gen. George F. Moore became the Harbour Defense Commander. It was under his watch that Malinta Tunnel would be put to the use that it was intended for twenty years earlier. Probably the most fitting tribute to this tunnel complex came from him when he said “Without the shelter afforded by the Malinta Tunnel…organized defense of the Philippines would have collapsed in its early stages”.

For me, Malinta Tunnel will always be one of the most interesting places to visit on Corregidor Island. Stories of hidden gold and ghosts have nothing to do with it. I should note that the information written above speaks only of cavities carved into the rock; there is no mention of the few thousand people who either temporarily lived here or who died within these passageways. History is the real attraction and it lurks everywhere you step.