Update on the USS Guardian MCM-5 Salvage Operation I received this just before I went to my wife’s province in May and so only now have the time wrap up this grounding incident. The below article was sent to me.

April 30, 2013

www.armytimes.com/article/20130430/NEWS/304300016Navy report outlines errors that led to Guardian's grounding

By Sam Fellman

Staff writer

On Jan. 17, the mine countermeasures ship Guardian drove through the Sulu Sea on a moonless night. The ship was headed from the Philippines to Indonesia and its track skirted two atolls, ringed by treacherous reefs and marked by a lighthouse — hazards the bridge team was only dimly aware of.

Thirty minutes after midnight, the electronic charting system flashed a “red danger” alert as Guardian entered a restricted area, according to an investigation. Not long afterward, a distant light came into view off the bow.

Assessing this complex situation fell solely to Guardian’s watchstanders, who received no brief or warning. The night orders, issued by Lt. Cmdr. Mark Rice, Guardian’s commanding officer, made no mention of the shoals, the lighthouse or whether to set a navigation detail, as is required when the ship passes close to shallow water.

One digital chart showed the ship was on a path to pass the nearest reef by three miles, so the presence of the light provoked interest that gradually became confusion: Was it a boat? The junior officer of the deck said it correlated to a slow-moving vessel on radar. The combat information center reported it as a radar contact to the bridge. And the chief quartermaster assessed it as the lighthouse on the reef’s southernmost point.

As the ship steamed forward at 10 knots, radar showed land, the light grew closer and confusion persisted. The lieutenant junior grade standing officer of the deck turned the ship away from the light, thinking it might be a boat, in order to avoid calling Rice, who was asleep.

Instead, Rice awoke at 2:20 a.m. when the hull shuddered.

He was summoned to the bridge, according to the Navy investigation. Guardian had run aground on the reef near the southernmost atoll, a position that the crew was unable to extricate the ship from. It would take Navy salvage teams two months to saw through the stricken ship’s hull and crane it in sections off the maritime sanctuary.

Navy investigators determined the cause of the wreck — which strained relations with a key ally and will cost the Navy an estimated $87.6 million, including $1.5 million in fines — stemmed from a series of navigation and watchstanding errors no one sought to resolve. Their report faulted Rice, executive officer Lt. Daniel Tyler, who also served as the navigator, and the leading quartermaster for widespread failures to comply with navigation standards. The report also concluded that proper route planning would have revealed a troubling discrepancy: The general and coastal digital charts disagreed on the location of the Tubbataha Reef, with the larger-scale coastal chart plotting it eight miles from the reef’s actual position.

“The CO, XO/NAV and leading quartermaster developed a voyage plan with a navigation track passing through the reef area without noting the hazards, [navigation aids] or providing guidance on how to manage this transit,” stated the afloat safety investigation report issued April 11 by the Naval Safety Center. “No action was taken to mitigate the hazards of the transit. The result was to default to the on-watch team.”

Rice, Tyler, the assistant navigator and the lieutenant j.g. standing OOD at the time of the grounding were fired April 3. Rice declined to comment in an email. Tyler did not reply to emails. The minesweeper was retired from the fleet at a March 6 ceremony in Japan.

Tubbataha Reef is surrounded by deep water, and a route adjustment of a few miles would have allowed Guardian to stay well clear, the report concluded, noting that the ship did not have permission to pass through Philippine territorial waters in the first place.

“Had the voyage planning process been properly executed in accordance with approved procedures, the transit in proximity to the reefs would have been avoided altogether,” the senior investigator noted in the 38-page report, which was obtained by Navy Times.

Navy officials declined to comment on specifics of the report.

“It is both unfortunate and unhelpful that an internal investigation, that includes privileged conversations, has made it outside the chain of command,” said Navy spokesman Lt. Cmdr. Ryan Perry, in a statement. “The intent of this investigation is to encourage open, frank and honest discussion of the events surrounding mishaps which leads to safer operations for Navy personnel worldwide.”

Perry said accountability is critical in cases such as this one.

“When a mishap occurs that reveals we weren't operating at our own standards, we thoroughly investigate the circumstances to ensure we understand what went wrong and learn from any mistakes made,” he said.

Missed chances

Faced with a confusing situation, some watchstanders initially took proper action. One of the two quartermasters of the watch, a 20-year old seaman, told the OOD that the ship had entered a restricted area after the Voyage Management System alert and recommended exiting it. When this didn’t happen, the same seaman suggested setting a navigation detail.

The OOD called Tyler, the navigator who was asleep in his stateroom. After hearing a brief rundown of the situation, Tyler determined a modified nav detail wasn’t needed, the report said.

An hour later, the OOD, a 24-year-old surface warfare officer, rang Tyler again. The ship was on track to pass another atoll within four miles, a distance that requires a navigation detail per the ship’s standing orders. The detail adds more people to the bridge and CIC navigation plots, allowing for more frequent fixes. But Tyler decided against it again. The report didn’t explain Tyler’s reasoning.

Required reports were not made, the report shows. The bridge team didn’t report radar landfall or the unexpected sighting of the possible navigation aid, which are required by the CO’s standing orders and would have given Rice time to intervene. They also had as long as 50 minutes to assess the light off the bow as a lighthouse, based on the flashes at five-second intervals noted on the chart.

The 35-year-old chief quartermaster on watch recognized that the light was most likely the lighthouse seen on the VMS’s electronic charts “but did not provide forceful back-up to the OOD,” the report concluded.

Rice’s failure to oversee the ship’s track and to note the hazards in his night orders set the stage. But bigger failures came from officers who knew there was some confusion, but didn’t slow down and notify the skipper, said one former cruiser CO who reviewed the safety report.

“I don’t believe the CO knew any of this was transpiring,” said retired Capt. Kevin Eyer. “The navigator — he did.” The OOD also deserves blame for never calling the CO, Eyer said.

But there are things the Guardian got right. The report hailed the crew for their quick response to the grounding, closing hatches to curtail flooding while the ship used engines and the anchor to try to free the ship. Those efforts continued for 32 hours. The sea drove Guardian farther onto the reef during the second night. With waves on the beam, Guardian was at risk of broaching. Rice ordered all 79 crew members to abandon ship Jan. 18. All did so safely.

“The engineering and [damage control] efforts, in the face of the given situation,” the report said, “were magnificent and maintained the Navy tradition of not giving up the ship.”

Additional Facts

GROUNDING TIMELINE

The significant steps leading up to the Jan. 17 grounding, according to a Naval Safety Center report:

9:27 p.m. After checking charts, offgoing officer of the deck assesses the ship’s track that night will pass within 3.6 nautical miles of a reef and explains this to his relief, who took the deck at 11:59 p.m.

12:34 a.m. Voyage Management System “red danger” alarm sounds as the ship enters a restricted area. XO determines navigation detail not needed.

1:30 a.m. Bridge team spots a flashing light off the bow and correlates it to a radar contact that appears to be moving at 3 knots.

1:36 a.m. Quartermaster determines the ship will pass within four nautical miles of a second island. XO decides against a nav detail again.

1:55 a.m. Quartermaster tells OOD the flashing light off the port bow is likely a lighthouse with a five-second flashing light, not a vessel.

2:03 a.m. Conning officer turns the ship starboard to open the passing distance to the light off the bow, to avoid calling the CO.

2:10 a.m. Bridge officers assess the flashing light as a fishing vessel, despite the quartermaster’s evaluation that it was a lighthouse.

2:20 a.m. A “major vibration” courses through the hull as the ship runs hard aground. All stop ordered.

2:25 a.m. After Rice and damage control assistant arrive on the bridge, conn orders “all back six.” It is unsuccessful.

9:18 a.m. High tide. A second attempt to get the ship off the reef, this time using both engines and the anchor, is unsuccessful.

At 3:20 the next morning, seas drove Guardian farther onto the reef and flooding became uncontrollable. The captain ordered the crew to prepare to abandon ship at 7:09 a.m.

SOURCE: NAVAL SAFETY CENTER

5 images and their descriptions have been uploaded here, they are out of order in the Photobucket album:

app.photobucket.com/u/PI-Sailor/a/6b824231-ae6a-4e22-88cf-cfbc2fea766a?field=TITLE&desc=ascThese pictures came from the US Navy Faceplate Magazine. This is a large PDF file:

www.supsalv.org/pdf/FaceplateMAY2013.pdfFACEPLATE is published by the Office of Supervisor of Salvage and Diving Director of Ocean Engineering (NAVSEA 00C) to provide the latest and most informative news to the Navy Diving and Salvage community.

Remember, I was a US Navy Diver.

These same 5 pictures from the US Navy Faceplate magazine are also posted here:

-US Navy Faceplate Magazine Cover Page

Salvage work on the ex USS Guardian MCM-5 is in progress.

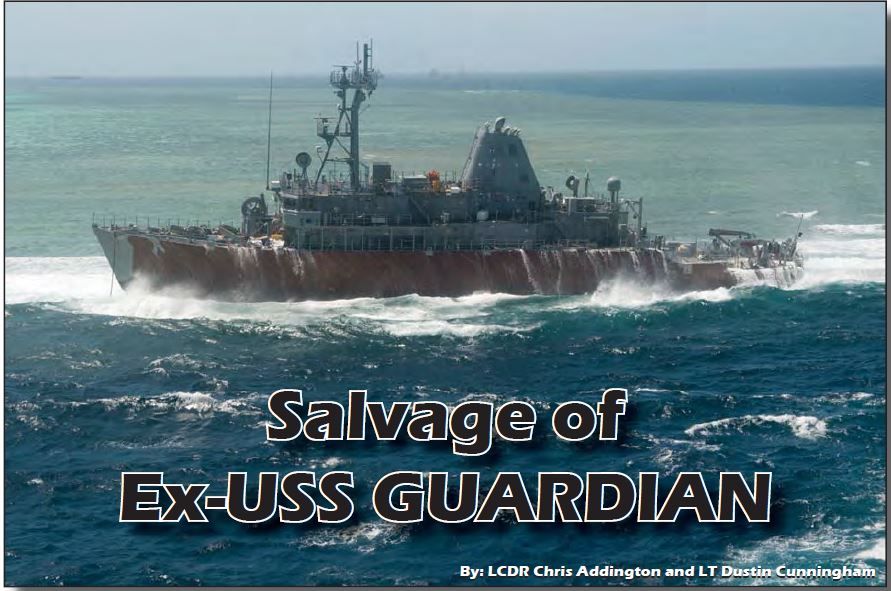

-USS Guardian in trouble.

These rough seas drove her deeper onto the reef and tore up her wooden bottom. This about the 18th Jan. 2013 or a few days later.

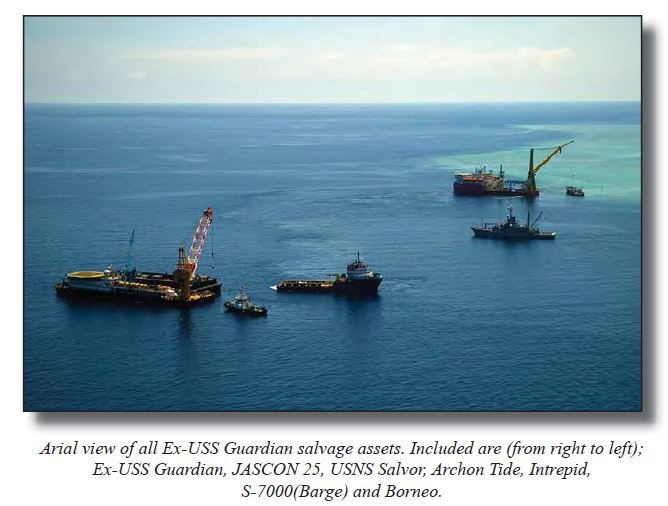

-USS Guardian Salvage Assets

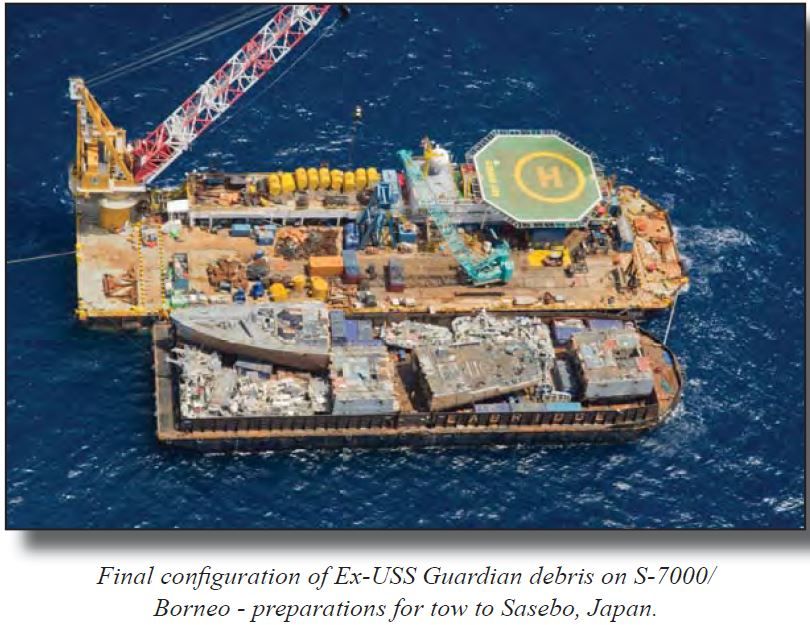

-Final USS Guardian Grounding Clean-Up

-The USS Guardian Salvage Job is done!